Alt-F4 #26 - Putting the Multi in Player 2021-03-05

In this week’s 26th issue of Alt-F4 (half a year of issues!), oof2win2 goes into the Factorio multiplayer and explains some of the technical machinations behind it. If you’ve ever wondered what a desync is or how the game manages to handle hundreds of players and many thousands of entities at once, please feel free to dive right in!

Factorio Servers oof2win2

Most of us have probably connected to a Factorio server at least once, to play with friends or just check out some else’s builds. In today’s edition of Alt-F4, I will briefly explain the history of multiplayer, and then I will take a deeper dive into explaining how multiplayer works technically. I will be explaining the usage of fully deterministic and lockstep algorithms, amongst other things.

The History of Multiplayer

In October 2014 with Factorio 0.11.0, multiplayer was introduced into the game though it has been worked on since Factorio 0.9.4. This multiplayer was unlike the one you see today, you couldn’t for example easily ‘Join Friend’ through Steam or use the server browser - you needed to know the exact IP address of the server. When the first multiplayer was released, there were quite a few bugs, such as this bug which didn’t allow multiplayer games to last more than 20 seconds. It was of course fixed, not even three hours later, in typical Wube fashion. There was also this bug which didn’t allow for three or more people to connect at once - unlike this 500+ player multiplayer session nearly six years later. A lot of work has been put into multiplayer development for 500 players to be able to connect at once.

In Factorio 0.12.0, as a major feature, headless servers were added. This meant that servers could now run on machines without GPUs, which greatly reduced the cost of Factorio servers and improved accessibility. It also allowed multiple server instances to run at the same time on one machine, which is very useful in some cases.

With Factorio 0.14.0, Factorio servers no longer paused the game for all players if one player’s computer takes too long to process an update. This means that if you have an older computer, a server will no longer wait for you to catch up in processing. This is very useful on larger servers which can have tens to hundreds of players online at once, as nobody has to wait for one single person so they can play the game.

A Fully Deterministic Approach

As mentioned in FFF-30, all clients and the server must simulate the game in the same way, the same actions at exactly the same time. This means that if one person does something on their computer, other people’s instances of Factorio need to do the same. An instance is an occurrence of something, for example, there can be many instances of apples in a basket or tabs in Chrome. Factorio is very different to most multiplayer games, like CS:GO or Overwatch, so the devs couldn’t just take the multiplayer implementation model from these, and port it to Factorio, as it wouldn’t work properly.

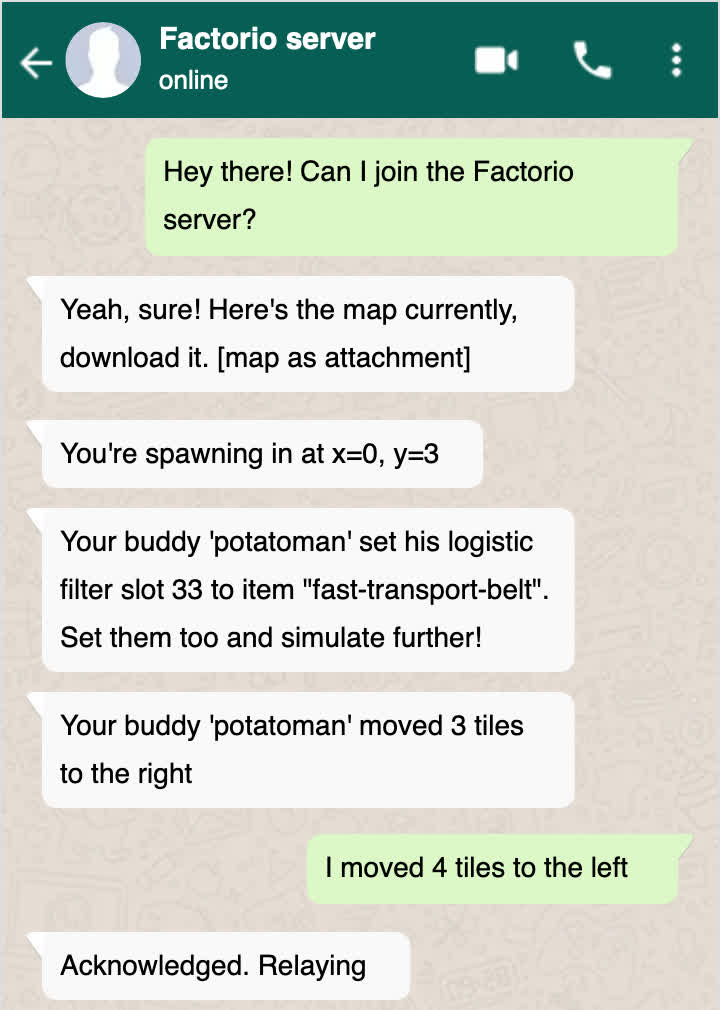

Instead, during the creation of multiplayer, the developers created multiplayer using the lockstep protocol. In Factorio, the connection to the server starts with the server giving you just the map. Then, the server only tells you if something changes by user input, such as if a player places a belt at some coordinates, dies from a biter (or a train), etc. You only get told that it happened then, your game has to update its local simulation by itself. It doesn’t get a detailed update every tick of all the things that are currently happening, such as bots moving and trains stopping.

Transmitting everything that happens, every single tick, would require a lot of network bandwidth, as you would need to transfer information such as “this logistic bot moved here”, which would need to happen tens of thousands of times per tick in large saves. Not to mention some other information, which would lead to transferring the whole save every tick, resulting in 1500MB per second of transfer in some cases. Instead, you only get told the really important information, which is mostly interactions of players with the game, and then your client runs the game as if nobody else was there.

There are many other ways a game can handle multiplayer. For example, Overwatch is a game that keeps track of almost everything, centrally on their game server, monitoring every item, player, bullet etc. and actively corrects your client if something went wrong. Factorio monitors only player inputs and throws a desync if something goes wrong. I’ll explain what a desync is later. These two implementations are different because the games are radically different: in Overwatch, you can have all the maps downloaded when you initially download the game, so you need to only transfer player and projectile positions. In Factorio however, maps change all the time.

In Factorio, you have different positions of assemblers, lamps, power poles, belts, inserter positions, and pretty much everything else, as every base is unique. This is the reason why in Factorio, only the changes caused by players are transferred, as Factorio can simulate the game as if it were singleplayer, just receiving player changes from the server. It is much easier to just give the client the map when they connect and tell them any other inputs that would alter the simulation, such as a player moving ten tiles to the right, rather than transferring the whole map, every tick. See the image below. For anyone curious, Overwatch multiplayer has been explained here (shorter video) and maybe here too by the Overwatch developers in more detail.

Fully deterministic algorithms are used in Factorio and such algorithms will produce the same output when given the same input. This means that there is no randomness in the results, which is required in some cases such as Factorio. A fully deterministic algorithm is required when multiple instances of Factorio are run so all instances run in a lockstep algorithm and are in sync. The reason for fully deterministic algorithms would be that if you have functions that produce random outputs, you can’t use the lockstep architecture, as the whole system screws up if the functions that process things don’t give the same results for each client, every time. A fully deterministic algorithm is defined by the following:

- It must not use any other data other than the input to the algorithm. Disallowed data: random numbers, stored disk data, global variables, timers (i.e. time from the startup of the program)

- The algorithm must operate in a way that is not time-sensitive

An example of the opposite of this would be if multiple instances of a program were writing into an Excel spreadsheet and another program would read the last line of the sheet. This would make the program time-sensitive as if one instance of the writing programs is delayed by a few seconds, it can produce a completely different order of the Excel rows, leaving the program that reads the last line with completely different input.

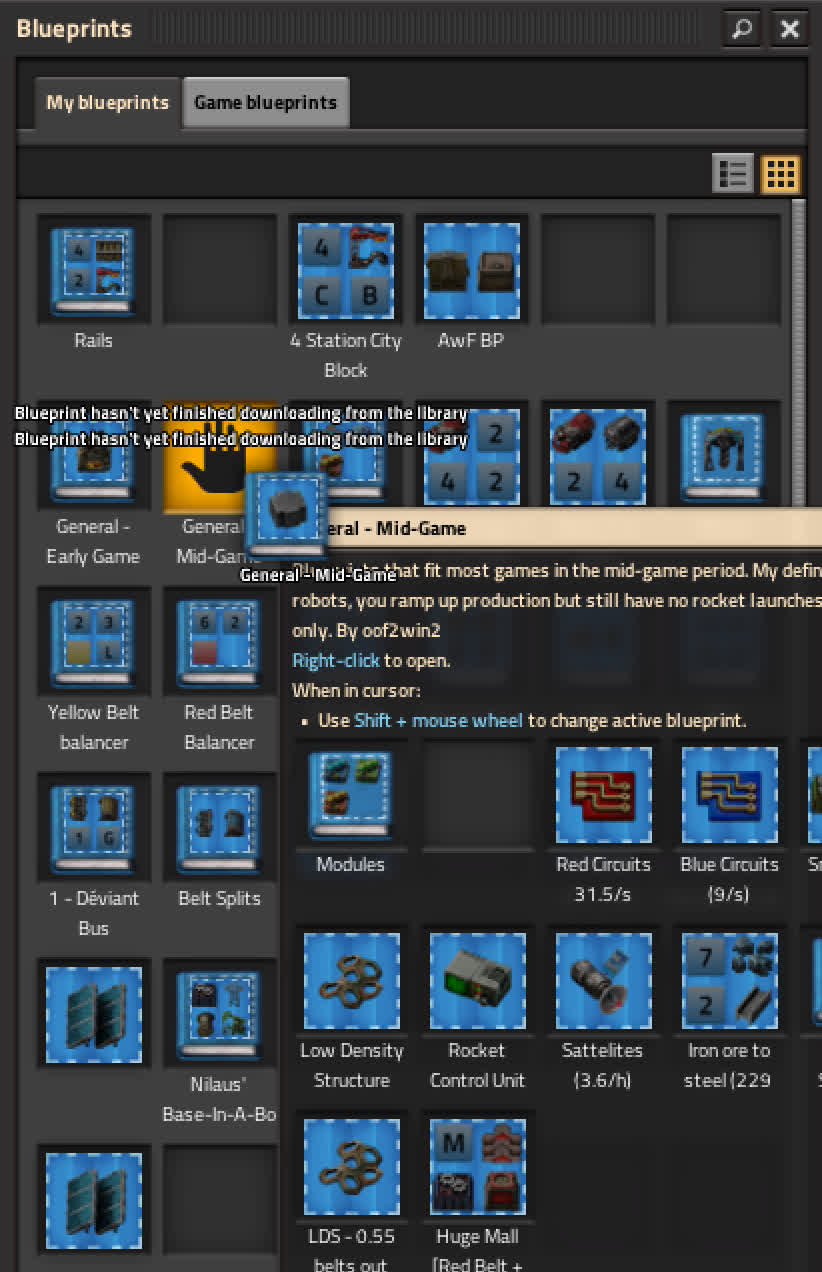

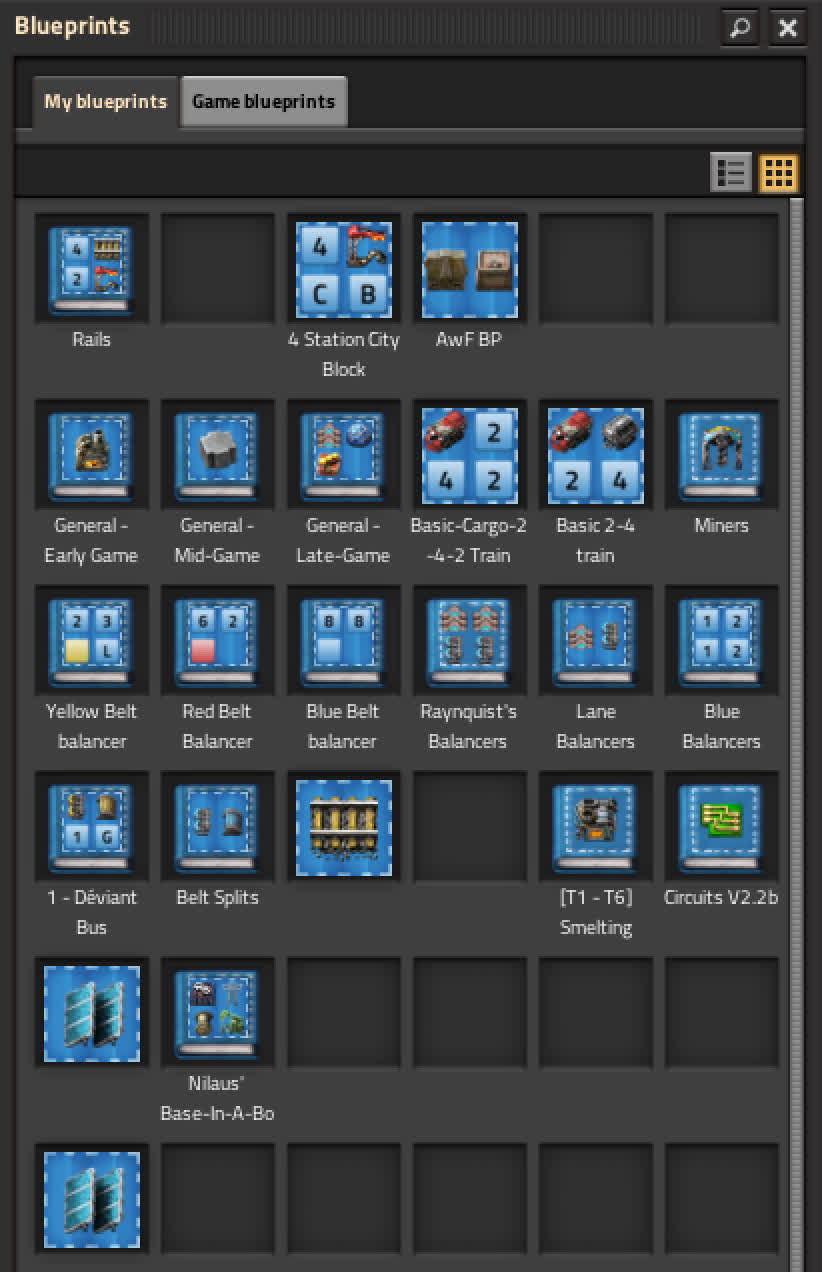

One example of lockstep and fully deterministic algorithms would be a client stamping down a blueprint. When you click on a blueprint to import the blueprint to the shared library, the blueprint icons won’t be greyed out anymore, such as the right-hand image below. This is because when you click on them, you choose to transfer them to the game’s shared library. When you then place it down somewhere, your client tells the server that you placed the blueprint down at certain XY coordinates. The server then tells all other connected clients that it has been placed down at those same coordinates. Every individual client then simulates all robots coming out of their roboports, getting resources, placing the entity they have, and coming back to their chosen roboport. All clients simulate this by themselves, without any further inputs, and do it in the same way due to the previously mentioned fully deterministic algorithms.

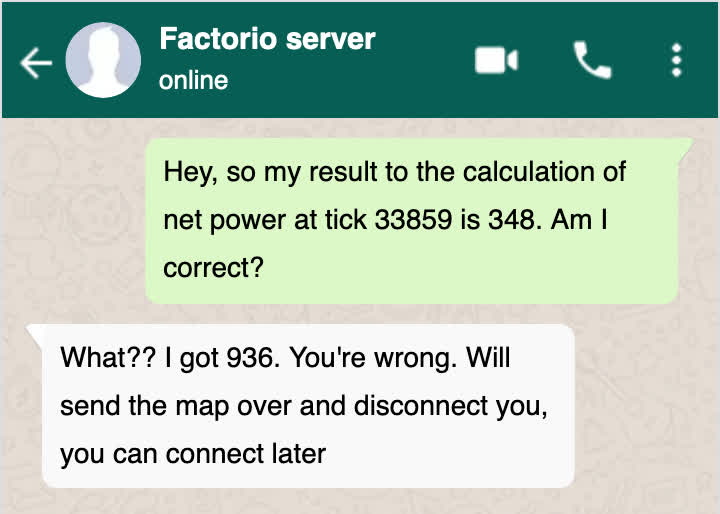

A desynchronization (‘desync’) is when two computers are supposed to be doing something at the same time with the same results according to the fully deterministic algorithms but don’t. Normally, when the client and server are doing the same thing at the same time, they are happy, as they are synchronized (‘in sync’). A desync can occur due to two clients calculating an update with different results, usually due to a programming mistake. See the image below for an example of how a desync can happen. If a modder or scenario creator doesn’t manage their data well, it can cause a desync too. A desync will make your client forcefully log off from the server and generate a desync report, which is something that the developers use to investigate these desyncs.

You may wonder, how do desyncs not occur with robots moving across the map? Surely if they all do tasks and some robots are chosen to do said tasks, different clients might choose different robots to perform those tasks, no? Nope. Every client will always choose the same robot at the same time because the algorithm that chooses the robot is fully deterministic. Two trains coming in from a stacker into a station? Always the same train, as this is also fully deterministic. Which turret does a biter decide to attack at your mining outpost? Also fully deterministic. These have been just a few examples, but everything in the game is fully deterministic. If it weren’t, you would have one desync here, another one there, and multiplayer wouldn’t be playable at all. In multiplayer, desyncs can be caused by numerous things, such as robot construction, biter AI simulations, and most of all, things caused by modders themselves.

Even if you would want to use something as simple as math.random() to get a random number in a mod or scenario of yours, there would be consistent results - all clients would get the same result of the function. This is because Factorio’s random number generator is seeded. It gets given some number to start with, which it then uses to generate random numbers over time. If you get every client seeded the same way, your random numbers will be in sync. It is important to note it is a pseudorandom generator, and therefore not truly random, as it is initialized with a pre-determined number, which allows the results to be reproduced anywhere. See this for more info on random seeds.

Now you know a bit more about what happens when you click on a server in the server list, join by IP, through Steam or over LAN. The developers of Factorio have been working very hard on multiplayer, allowing us to create large games such as the over-500-player multiplayer session or complex Clusterio setups, providing creators with tools they need to develop the fun stuff they do. There are fewer and fewer limitations to what you can do, massive bases, massive amounts of players, maybe even both! All of that is up to you and how you set it up.

Contributing

As always, we’re looking for people that want to contribute to Alt-F4, be it by submitting an article or by helping with translation. If you have something interesting in mind that you want to share with the community in a polished way, this is the place to do it. If you’re not too sure about it we’ll gladly help by discussing content ideas and structure questions. If that sounds like something that’s up your alley, join the Discord to get started!