Alt-F4 #61 - Draftsman: A Python module for creating blueprints 2022-05-27

For this week’s issue of Alt-F4, we return to the roots of being a spiritual successor to the FFF by going deep on a technical topic. To that end, redruin1 presents his newest invention: Factorio Draftsman. Sure, there have been other projects trying to build a library for generating blueprints for the game, but this one tries to be the new gold standard. Motivations, technical details, and a few fun projects realized with it - all that, and more, this week!

Draftsman redruin1

A couple months ago, I decided that I wanted to try my hand at making a self-expanding factory in Factorio. After seeing a number of impressive examples, I was inspired to have a go at the problem. I already had an outline of the logic, and how the factory would keep track of itself, as well as lofty ideas on impressive things that I could make it do. The only trouble was that I had actually never used combinators before, and I was planning on using them for the actual decision-making.

That’s no problem, though: We just create a scrap world, switch to the editor and start playing around!

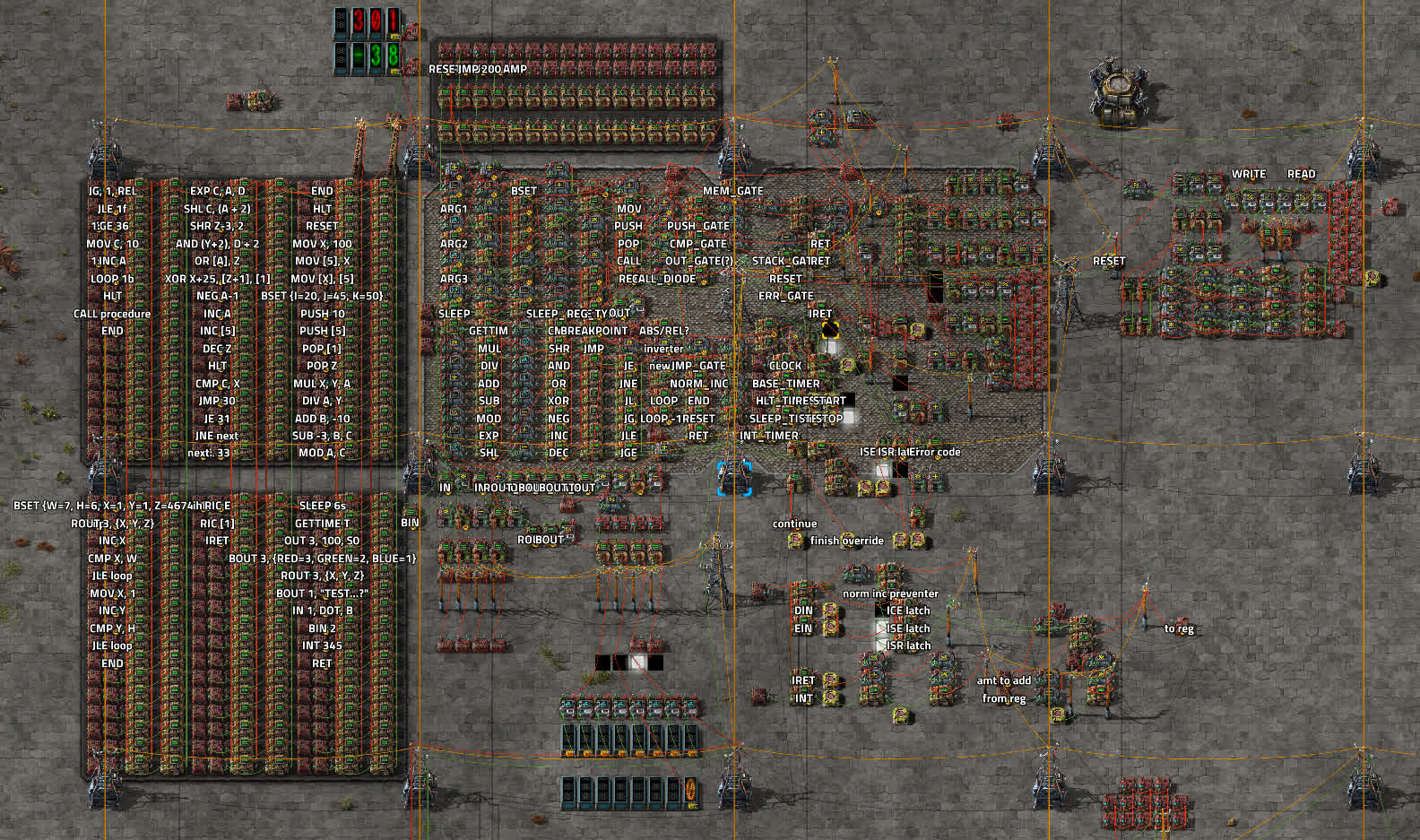

I may have gotten carried away a little.

Here’s a CPU I made. This is the seventh (I think?) revision. It has a ROM, RAM, a stack, 256 registers, over 40 instructions, breakpoints and code stepping, hardware and software interrupts, as well as a generalized circuit interface to interact with other machines.

Ironically, I’m not actually here to talk about any of this. This is all just foreshadowing.

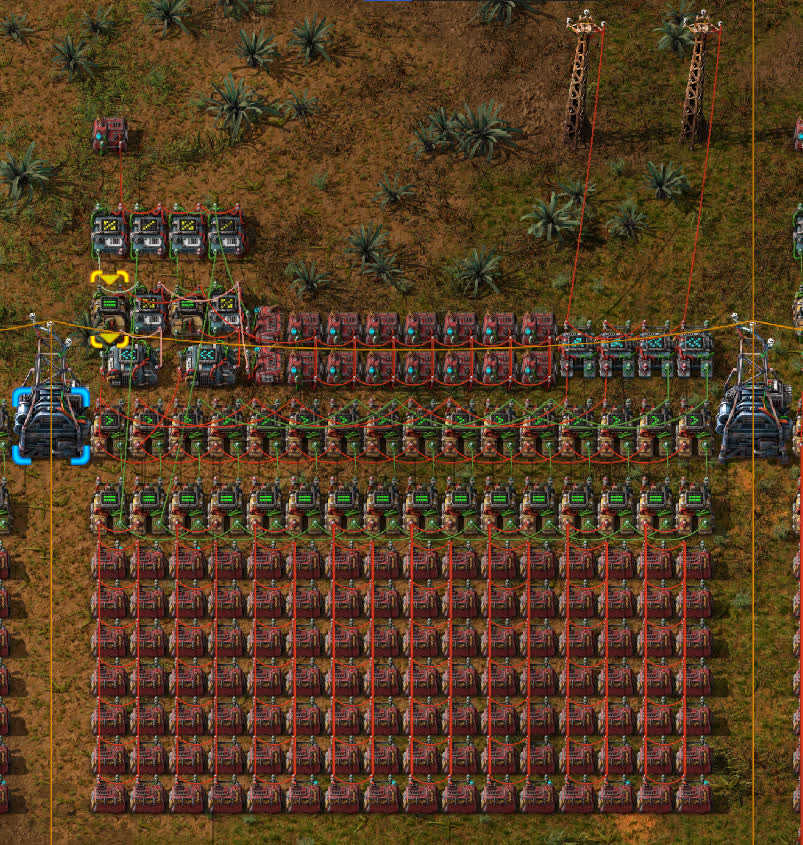

I was starting the second revision of the computer and I wanted a more compact ROM. I came up with the design below, which has the capability of storing true 32-bit numbers and can store 4 KiB of data per row:

The ROM is very dense, but it functions on a system where each value is split into and stored as two 16-bit numbers, which are then recombined on output. ROMs are normally tedious to create, manually encoding each signal you want by hand, one at a time, but this design was even more involved. I now had to split, bitwise AND, bitwise right-shift, and populate not one signal, but two, in two different specific locations, making sure that they both had the correct value and signal type. Needless to say, it was going to be painful to set tens of values, let alone hundreds, or the thousands the machine was capable of storing.

The solution? Get a computer to do it for me. It can stomach this task far better than I ever could, and can do it way faster as well. Factorio’s blueprint string import function can take any correctly formatted string; all I had to do was create this text string to my specification with the data I wanted and I could just paste it where needed.

This concept is not new, at all. Even a cursory search will turn up numerous examples of this used in practice: factorio-blueprint NPM module by demipixel, justarandomgeek’s compiler for his massive combinator computer, a generic combinator instruction language by Jobarion, image-to-blueprint converters, etc. The list is extensive.

With all these examples, I was hoping that I could find some similarities with one of them and use that as a baseline for my solution to avoid “retreading” the same ground. Something troubled me about the solutions that were available though: They all had problems!

- Many implementations were highly specific to the domain they were written for; a combinator computer compiler script was not going to be portable for many other purposes than compiling code for a specific combinator computer.

- They lacked a unified language; many were written in Lua, some in Python, another in JavaScript, one in C++, etc. This meant that each one had to write their own implementations for the same operations, instead of just having someone write the implementation they need and making it available to others.

- Many of them were written for versions of Factorio that are now severely out of date.

- Documentation for a lot of these modules was sparse and sporadic, which turns off users like me who want to know what the module is capable of before investing any time into learning how to use it.

Fundamentally unsatisfied with the options, I resigned myself to my fate. I was going to have to follow in the footsteps of all before me, and develop my own implementation from scratch. How arduous!

I made a prototype script in an afternoon that did exactly what I needed and it worked perfectly. It used a template system and it took less than a week to completely finish.

But then I started to wonder. It wouldn’t be that difficult to update a module like factorio-blueprint to modern Factorio, and I bet I could figure out some way to automatically extract the data from Factorio itself, so you would never have to manually update source files every version. Then I started getting lofty ideas about how I could write documentation for the complex and largely undocumented control_behavior key in entities, or adding custom entity types to create and manipulate groups of entities, or even, god forbid, adding mod support into the mix. That was three or four months ago.

Anyway, here’s a Python module I made.

Introducing: factorio-draftsman

Draftsman is a Python module for creating, modifying, importing, and exporting all manner of Factorio blueprint strings. The package allows you to create and design blueprints programmatically, to aid in the development of tedious and repetitive blueprints that would be untenable to create by hand, much like the problem I ran into described above. Draftsman attempts to solve all of the shortcomings of existing Factorio blueprint implementations:

- Draftsman does it all. All types of entities are supported, from splitters to stack inserters. If you can do it in-game, you can do it with Draftsman, allowing you to focus on the one problem you’re actually trying to solve.

- Draftsman is uni-language. Written in Python, this makes it exceptionally easy to install, simple to use, and gives the user access to the entirety of Python’s vast packaging index. Chances are you can do it in Python with Draftsman, regardless of what Factorio-related thing you’re actually doing.

- Draftsman is easy to use. Designed from the start to be simple and (most importantly) self-documenting, Draftsman allows you to manipulate blueprints and entities by auto-completable attributes and methods.

- Draftsman is well-documented. Every function, method, attribute, and class is documented and crosslinked at its readthedocs site. In addition, tutorials and supplementary materials are provided, as well as a whole host of example programs to help illustrate how Draftsman works.

- Draftsman is stable. A rigorous suite of tests ensure that Draftsman behaves predictably and correctly (or at least correctly enough), with a code coverage of 100%. Draftsman is verified to work on the latest versions of Python 2 and 3, and is compatible with all versions of Factorio greater than 1.0, with the metrics to prove it.

- Draftsman is descriptive. Draftsman enforces “Factorio-safety” as a core philosophy, which means that if a blueprint would have an import error in Factorio, an exception is thrown by Draftsman. Draftsman also tries to enforce “Factorio-correctness”, which means that values that won’t break, but are otherwise nonsensical, will raise warnings. Both errors and warnings are verbose, so that any problem with your script can be understood and resolved in seconds.

-

Draftsman is close-to-source. Draftsman bases all of its data off of Wube’s

factorio-datarepository, which means that all entities are exactly as you would expect in-game, with no inconsistencies. This makes Draftsman up-to-date, makes updating Draftsman for future Factorio versions a breeze, and allows version control to monitor changes between Draftsman and Factorio, if any future breakage should occur. - Draftsman supports mods. Draftsman emulates Factorio’s data lifecycle directly, meaning that the same loading process that happens when you launch the game is mimicked with a single Draftsman function. In addition to ensuring absolute accuracy to Factorio, this also means that custom mod prototypes can be accessed from Draftsman as if they were any other vanilla entity.

Draftsman has custom classes designed around each individual entity and prototype, and is designed to work as seamlessly as possible with blueprint strings and other software. Draftsman converts to and from these prototypes when you import and export blueprint strings automatically, no extra steps required. You can import a blueprint string from Factorio as a Blueprint object, make any change you want, and then export that Blueprint object back into a string. Or, you can just make an entirely new Blueprint from scratch; Draftsman is designed to work around you, not for you to work around it.

Draftsman also has support for custom "EntityLike" objects, most notably Group objects, that allow you to create custom constructs that can be inserted into blueprints for aid with clarity and compartmentalization. For example, you can make a design for a smelting block in a Group, and then you can place that block as many times as you want, wherever you want, rotated or flipped, essentially acting as a copy-paste tool within Draftsman.

In an effort to keep this article brief, I’m not going to go too far into the nitty-gritty about the module or how exactly it works; I’ve spent a lot of time writing documentation for that purpose instead. Rather, I’m going to show off a couple of things that I’ve made with it so far, as well as potential things that could be made in the future, to try to illustrate exactly why I spent all this time making it in the first place.

Automatic Item Stack Sizes

Oftentimes, for you want to figure out how much storage you need for a specific amount of an item. However, storage in Factorio is based on slots, not amounts, so the amount of storage is actually dependent on not only the amount you’re trying to store, but also the stack size of that item. You can design a circuit contraption to determine the number of slots that you need for any input item, but you’d need a big cell of combinators documenting the item sizes. This is boring to make, and easily broken if a new item is added or the stack size is changed. Clearly, for such a simple and repetitive task, a script is better suited:

# Create an N x 5 grid of connected constant combinators, with every item and their stack size

from draftsman.blueprintable import Blueprint

from draftsman.constants import Direction

from draftsman.data import items

from draftsman.entity import ConstantCombinator

COMBINATOR_HEIGHT = 5

def main():

blueprint = Blueprint()

signals_added = 0

signal_index = 0

combinators_added = 0

x = 0

y = 0

combinator = ConstantCombinator(direction=Direction.SOUTH)

# Iterate over every item in order:

for item in items.raw:

# Ignore hidden items/entities

if "flags" in items.raw[item]:

if "hidden" in items.raw[item]["flags"]:

continue

# Keep track of how many signals we've gone through

signals_added += 1

# Write the stack size signal

stack_size = items.raw[item]["stack_size"]

combinator.set_signal(signal_index, item, stack_size)

signal_index += 1

# Once we exceed the number of signals a combinator can hold, place it and reset

if signal_index == combinator.item_slot_count:

# Add the combinator to the blueprint

combinator.id = "{}_{}".format(x, y)

blueprint.entities.append(combinator)

# Reset the combinator

combinators_added += 1

y = combinators_added % COMBINATOR_HEIGHT

x = int(combinators_added / COMBINATOR_HEIGHT)

combinator.set_signals(None) # Clear signals

combinator.tile_position = (x, y)

signal_index = 0

# Add the last combinator if partially full

if len(combinator.signals) > 0:

combinator.id = "{}_{}".format(x, y)

blueprint.entities.append(combinator)

# Add connections to each neighbour

for cx in range(x):

for cy in range(COMBINATOR_HEIGHT):

here = "{}_{}".format(cx, cy)

right = "{}_{}".format(cx + 1, cy)

below = "{}_{}".format(cx, cy + 1)

try:

blueprint.add_circuit_connection("red", here, right)

except KeyError:

pass

try:

blueprint.add_circuit_connection("red", here, below)

except KeyError:

pass

print("Total number of item signals added:", signals_added)

print(blueprint.to_string())

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

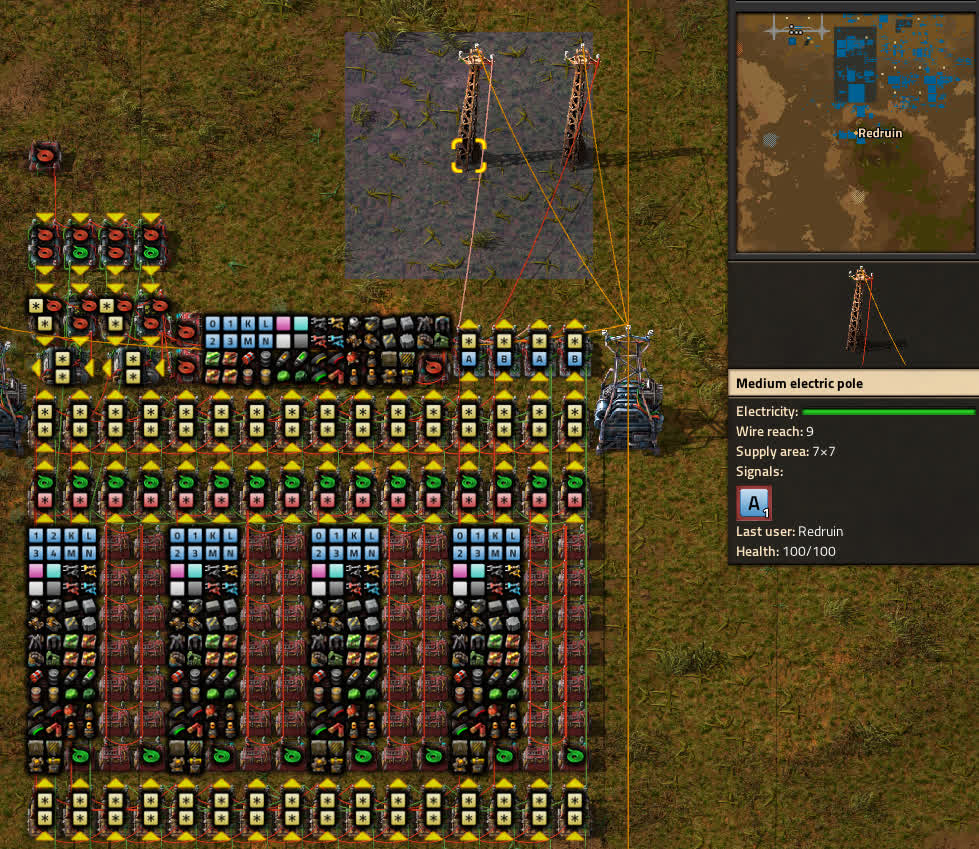

This script is concise and easy to follow, but the really amazing thing about Draftsman is that this script is completely dynamic and can adjust to whatever version of Factorio that you’re playing. New items, removed items, or changed stack sizes, regardless of the author of the change, are resolved automatically with the exact same code. For illustration, pictured top-left is what’s generated by running the script for a vanilla game, top-right a game with the medium-sized overhaul modpack Space Exploration, and at the bottom a Bobs + Pyanodon mega-modpack:

This doesn’t only apply to items either. All entities, instruments, signals, recipes, modules, and tiles are pulled from the emulated load process and then stored in Draftsman for later use. Any script can be designed to be completely flexible across these categories; extra instruments in a new programmable speaker, new module types only in certain machines, complete virtual signal lists for signal mappings, etc., all are interpreted correctly by Draftsman. By saving the data of the current mod configuration internally for later, this also means that you only have to update the data once, each time you change what mods you’re using.

Image to Blueprint Converter

This was something I made on a whim. It uses the Pillow image library to load an image, and converts it to a blueprint intended to be visible from the map view, all in less than 150 lines of code:

Many improvements could be made to this:

- Dithering is only implemented on 1x1 tiles; I was having trouble adjusting the algorithm to multi-tile entities.

- Multi-tile entities also fail to adjust the error metric property; palettization doesn’t work as well when some pixels are of different sizes.

- Some multi-tile entities have different rotations; a better implementation would check which orientation produces the least error before placing, instead of only placing them with the default orientation.

- The colors themselves are hardcoded; it would be nice to dynamically load this from the game, especially with modded map colors…

Despite these shortcomings, the output actually ends up pretty good for its quick and dirty implementation. This shows that Draftsman is versatile enough for some rather eclectic purposes.

Factorio Movie Player Resurrection

A little while ago, while trawling for projects to use as examples for this very article, I came across the classic Factorio Sandstorm. A perfect project to adapt; or, it would have been, if I could actually load the map in-game! The original map version was still dated to the tender version of 0.14.20. In addition, a lot of the migrations that took place over such a long span of time broke the functionality of the script to convert the image frames into map data, as well as some functionality of the map itself, so just downloading an old version of Factorio and coercing it along wasn’t going to be enough to revive the old save. For example, the build.lua script in charge of encoding still called the automation-science-pack and logistic-science-pack items science-pack-1 and science-pack-2. That should give you some indication of how old the map was!

It troubled me, seeing such an iconic piece of Factorio history fall into disrepair. So I took the time to fix the issues and migrated it all the way to 1.1.57:

Changing the build script could be done by hand, but the signal raw-wood that the machine internally used no longer exists in modern Factorio. In order to fix it, I replaced all occurrences of the signal with it in the map with artillery-wagon (since I knew it would be unique), and that map updating was done with a script running Draftsman code. I also added a number of other scripts for extracting the images from the source, as well as taking screenshots of the result and stitching them into an output video, which is pretty easy in Python. I used said scripts to make the output above.

I was also playing around with the idea of using Draftsman to make a blueprint-based version of the builder script, instead of the console-based original method; this would allow you to see exactly what parts of the memory you are modifying by placing a grid aligned blueprint on top of them, and would also allow you to extend the memory of the machine by simply adding more blocks (the memory provided on the map is only enough for 4800 frames). I figured this was less important than updating what was there originally, especially when the code that was already there I knew worked. There could be other considerations as well; the amount of encoded data is pretty hefty, especially for blueprint strings which I suspect may be less dense than the console scripts, which are so large they are dumped in text files when built. Determining whether a blueprint method was actually feasible I figured could wait until I had some spare time further down the line.

For more information on what’s changed/new, as well as the updated world file, you can check out my fork here.

What’s next?

While I’ve done a bunch of things with this module, the whole point of it was to make it easy for anyone to do a whole bunch of other things as well. Some ideas that I would like to do, but have yet to do, I will defer here as food for thought:

-

Many combinator computer compilers are written via script. Perhaps someone could devise a LLVM equivalent; a generic compiler, where you can tell it what instructions your CPU can perform and have it compile high level, established languages like C. Perhaps you could even use LLVM itself?

-

Take advantage of edge case behavior for specific optimization problems. Did you know that you can set entities to request any item, not just modules? You can only request items when originally constructed, which limits its usefulness somewhat, but robots will fulfill the request, allowing you to “kickstart” production in some cases. With something like the Recursive Blueprints mod, by placing assembling machines with item requests, and then deconstructing them when they’ve finished consuming their inputs, theoretically you can build a fully automated factory with only construction bots. Perhaps the Micro Factory can be further optimized? Or a new goal could be to have the fewest total number of entities to launch a rocket without user input?

A perhaps more generally applicable use case is this blueprint, a single gun turret that automatically requests 200 red ammo from the logistics network when placed. This is particularly useful in offensive efforts on large biter nests, as you can spam turrets around you and the bots in your inventory will create the turrets and deliver the ammo automatically, allowing you to focus on not dissolving in spitter goo.

-

Routing problems; pass in a set of outpost points and use an algorithm to automatically connect them to minimize distance, number of crossings, etc. Perhaps you could have it read from save files themselves?

-

Combinator contraptions are usually very complex and unintuitive for the layman to decode, as I have found out during my extensive exploration in the introduction. This is due to the density of the circuits, the hidden operations of each combinator, the rat’s nest of wires that is generated with no way to cleanly route them in small areas, and the inability to give labels to combinators or the wires that connect them. It would be nice to have a piece of software that can do take a blueprint string input, and allow the user to do all of the above to create easily decodable and understandable documentation for complex circuit contraptions. I’d love to use such a thing to create vectorized circuit diagrams for my computer. When I finish it. Eventually.

-

Use constraint satisfaction to design blueprints. I’ve experimented with this in the past, and it should be possible; assuming you can get the time complexity down from

O(MFG). If I end up writing another article for Alt-F4, it might be on this. -

You can also use neural networks for the previous goal; this is Python after all! I wonder if you could actually get some usable blueprints this way. Perhaps if you train it on the entirety of factorio.school…

Hopefully that should give the creative ones among you some interesting ideas. And maybe, just maybe, when someone needs to write a script for some specific problem to save themselves some time, they can actually save themselves some time instead of spending three to four months writing a Python module from scratch.

Eh, it was still pretty fun to make. Educational, too.

Ah, finally. Back to real work.

Contributing

As always, we’re looking for people that want to contribute to Alt-F4, be it by submitting an article or by helping with translation. If you have something interesting in mind that you want to share with the community in a polished way, this is the place to do it. If you’re not too sure about it we’ll gladly help by discussing content ideas and structure questions. If that sounds like something that’s up your alley, join the Discord to get started!