Alt-F4 #18 - The Road to Clusterio 2.0 18-12-2020

As the year draws to a close, we picked two mod-related topics for this week’s 18th issue of Alt-F4. First, Hornwitser gives us some insight into the long development progress of Clusterio 2.0 and the challenges that it poses. Then, DedlySpyder talks about their process of developing a simple mod and the compatibility challenges they face.

The Road to Clusterio 2.0 Hornwitser

I want to tell the story of how I ended up spending a year developing Clusterio 2.0, which still has a long way to go before a release. If you haven’t heard of Clusterio before, it’s open source server software written by Danielv123 (with contributions from around 30 others) that enables mods to interact across servers. It is perhaps best known for the Clusterio 60k event in 2018 where teleport chests were used to transfer items between some 46 Factorio servers in order to build a vanilla-like factory that could do 60k science per minute. These teleportation chests work like active provider and requester chests; one removes items from the game and puts them in shared cloud storage and the other takes items requested from that cloud storage and puts them in the game.

Clusterio has always been composed of two parts: the gameplay interactions that are implemented in mod code and run inside the game, and the server-side infrastructure which deals with moving data between the various game servers. In the beginning, the server side was coded around handling the teleportation chests, but as development progressed and more and more features were added the idea of what Clusterio is changed from teleporting chests to a modular server-side platform for making such cross-server gameplay elements.

In July 2019, The Gridlock Cluster event was held. Instead of teleportation chests for transporting items between servers, there were trains that could teleport from the edge of one server to the edge of another server using teleporting train stops. The code for teleporting the trains was implemented by Godmave as a plugin to Clusterio.

Sadly, the code was plagued with issues, which is where I enter the picture.

Humble Beginnings

I started out hacking on the Clusterio codebase back in July 2019 as part of trying to help the Gridlock team with the many issues they had. Servers were going down left and right, players were having issues, and new bugs and problems seemed to be cropping up by the hour. It was hectic, but there was also quite a lot of fun to be had. The event had sparked my interest in the code behind Clusterio, and after the event I took it upon myself to improve this code for the next event. That turned out to be a far greater project than I could possibly have imagined.

I’ve steadily worked on Clusterio 2.0 for around 16 months now and my estimate for when it’s done is still the same “just a couple of months” that I started out with. Despite this, my motivation to keep working on it remains strong, and one of the things I find particularly motivating is putting all this work to the test by organising my own Clusterio event. I have put out a teaser on Reddit for what I have in mind and right now the aim is to run it early next year. Possibly January, though only time will tell when it’s all ready.

But back to where it all began for me. I was installing Clusterio on my server, trying to set up my own test cluster in order to work on fixes for the issues encountered in The Gridlock Cluster. One of the first things I noticed was the one thousand packages it pulled in as dependencies, taking up over 300 MB of disk space. For this project to need that many libraries to function seemed preposterous. Node.js was new to me then, and while I’ve learned now that this isn’t actually such an unreasonable number of dependencies for a Node.js application to have, it’s still a lot. It was an indication of the sort of development style that had been used in the project: a top-down approach of adding features in whichever way was the simplest and quickest to implement there and then.

This style of development had led to the accumulation of a lot of technical debt, and I mean a lot. Technical debt is a term often thrown around in software development. It’s the idea that choosing shortcuts in development to save time often creates more work down the line when maintaining and extending the code base. In some ways you could say Clusterio was more a collection of hacks piled on top of each other than a well thought out and structured project. One memorable example of this was the inclusion and usage of four different HTTP clients in the same source file. Usually one such client is more than enough for a whole project, but presumably certain things were easier to do with one client compared to others and as time went on, different clients piled up.

So, I got to work on improving and cleaning up the Clusterio codebase. One of the first things I did was slimming down those one thousand or so dependencies. It turned out that most of it wasn’t actually needed to run Clusterio. About half were development tools that didn’t need to be installed in a production environment and a quarter were what I would describe as quick solutions: large libraries pulled in to use a single function from it. Many of these libraries were trivial to remove, either by reimplementing the function locally or by using another library that was already a dependency of the project. In the end I managed to remove the need for some 700 packages (244 MB), though it should be noted most of these were dependencies of dependencies.

The next issue I tackled was the automated testing. If you’re unfamiliar with automated testing, it is the idea of writing code to verify that the main code works as it should and doesn’t break with future changes. Automated testing is sort of a cornerstone for writing reliable code and while there were extensive tests set up at some point, they didn’t work when I got into the project. It’s another example of technical debt rearing its ugly head. Maintaining the tests, and adding new tests to cover new code, is extra work; skipping that work is a shortcut.

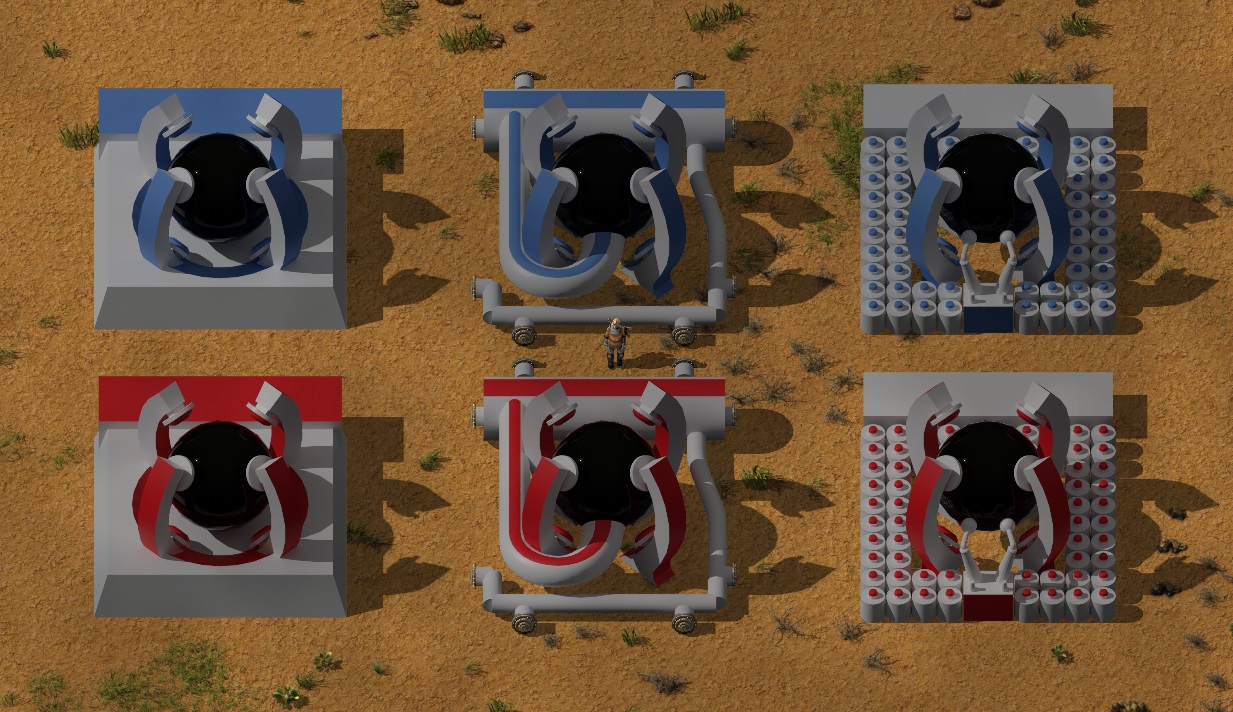

After the tests were fixed, my focus turned to cleaning up the code itself. Doing things like fixing broken code, removing unused or obsolete code, and refactoring bad code into slightly less bad code. One of the changes that started to take shape was moving the code for the teleportation chests out of the main codebase and into a separate plugin. Since Clusterio is first and foremost the server software making cross-server mod interactions possible, having these teleportation chests also called Clusterio is confusing when we’re expecting more and more that Clusterio will be used for other things than those chests. So we also decided to rebrand the item-teleportation-through-magical-chests feature as Subspace Storage. While I was at it, I also decided to replace those wonky sky chest and collection net sprites with something more appropriate to subspace storage.

They are still more of a placeholder though, since I’m not much of a 3D artist when it comes to texturing and mechanical modelling. I took the time to set up an automated toolchain with Blender to render, crop and output the sprites into the mod. You know how it is with programmers: automate all the things.

Save patching

As my work continued, the first major improvement I worked on was save patching, but before I talk about it I want to give some context to the problem it’s trying to solve. The game engine permits modifying the behaviour of the game with Lua code through mods and/or scenarios. Mods are loaded when the game starts and updating them requires restarting the game. Scenarios are Lua code packaged with the game saves and changing to a different scenario code requires only loading a different save.

When game-changing behaviour is put into scenario code, it’s often called soft-modding as you don’t need to download any mods and restart Factorio in order to join a server using such scenario code. While it’s easy to update a mod and continue an existing save, it’s not as straight forward with scenario code. There’s essentially three ways to update scenario code in a save, which I will list out roughly in the order of difficulty to implement:

- For scenarios distributed via a mod it’s possible to add a migration script in the mod that updates the scenario when the mod is updated. While this is quite simple to do, it comes with the major drawback of requiring the mod to be installed to run the migration.

- You can replace the scenario code stored in the save while the game is not running. This is what I call save patching and it’s relatively simple to do as the saves are regular zip files and the Lua code is stored in them as ordinary text files.

- You could also use the dynamic nature of Lua to load and execute new code while the game and scenario is running. This option is by far the most complicated but comes with the power of being able to apply fixes to the game while a map is running. The drawback is that it’s complicated to implement and get right, increasing the chances that something will go wrong. Additionally, the only way to send data to a running game is via commands, which gets problematic when they are long.

For the Gridlock Cluster the third option was done via a scenario called Hotpatch (also known as Server-side Multi-mod Scenario). Conceptually, Hotpatch is a very cool thing; it lets you load in mod-like code while the game is running, and it’ll execute that code in an environment that emulates the Factorio mod environment. But there were major issues with using Hotpatch: it’s poorly documented, making it hard to use correctly; the implementation was incomplete and buggy; and the most troublesome issue was that the updated scenario code was sent as long commands on start up. This meant that if players joined a server while it was starting up and in the process of sending those long commands to update the scenario, things went haywire, which is just one of the many ways the servers at Gridlock failed.

While many of the issues with Hotpatch have been fixed, the complexity and difficulties of working with it have taught me a valuable lesson: having advanced capabilities like being able to fix code at runtime, or technical marvels of any kind for that matter, does not always justify the complexity and issues that such advanced systems face. I got to experience this first hand when trying to fix issues that Hotpatch had a part in: everyone in the crew (myself included) struggled to understand the system and how to solve the issues with it.

For that reason, I decided to replace the role Hotpatch had in Clusterio with something simpler: save patching. It’s a less capable solution with more limitations on how code is written, but the simplicity in the way it works more than makes up for it.

Breaking Everything

After I implemented save patching, it became clear that a major overhaul of the code was needed. A particularly painful point about Clusterio has been the complete lack of remote management. If you want to start a Factorio server that is part of the cluster you have to log in to the computer that hosts it and manually start it through whichever process manager you choose to use, the same goes if you want to change any settings for that server. Managing a cluster in this way is painful and that was a lesson learned the hard way in the Clusterio 60k event.

For Gridlock, the Pterodactyl game server management panel was used to manage servers remotely; a good idea that turned out to be the cause of a lot of issues. But that’s a story for another time.

Having the ability to remotely manage Factorio servers in Clusterio has been a desired feature for a long time and there have been attempts at implementing it. Those attempts were more of an afterthought though, and due to the way the code was structured (running a single Factorio server per Node.js process) it became very difficult to implement any sensible remote management without doing a major overhaul of the code and breaking everything in the process.

So naturally I broke everything and implemented remote management.

The way Clusterio 2.0 works is that a slave process is run on each computer you want to host Factorio servers on. These Factorio servers are called instances in Clusterio and the slave process connects to the master server and listens for commands to create and start instances. Multiple instances can run at the same time on a slave, which means you only need to set up one slave for each computer you want to host Factorio servers on, and there’s only one Node.js process to start up on these computers.

Another thing that had to change was the way Clusterio communicated between computers. In version 1, this is handled for the most part by the master server hosting an HTTP server and responding to requests on it. This has the problem that the master server can’t send messages to other computers, only respond to requests sent to it from other computers; that’s how HTTP works. To get around this I replaced HTTP with a simple WebSocket based protocol using JSON payloads. WebSocket, unlike HTTP, allows both parties of the connection to send messages to each other at any time.

With everything now broken, this sort of became the point where the 2.0 development really began. I used this opportunity to start fresh on a lot of things in the subsequent months.

I hope you liked this glimpse into Clusterio 2.0 development. As you might imagine there are many more things about 2.0 that have happened in the past 16 months, certainly enough for more articles on the subject. Please note that 2.0 is not yet ready for production use, though if you’re interested in the development and want to test it out, check out our Discord server and GitHub repository.

Moddability: The Birth of a Mod DedlySpyer

Something kovarex said in FFF-363 stuck with me:

This is an example of a feature, that I just HAD TO DO, because once I realised that the feature could be there, I was almost trying to use it and was annoyed by the fact that it wasn’t there.

— kovarex

I’ve dipped in and out of playing Factorio for around six years, but since I started modding I’ve always loved tinkering with the game. Sometimes when I play, I end up seeing something new that bothers me just a bit and for which there isn’t a mod to fix it. I’ll get to a point where I just end up modding it myself. Normally, this causes me to discard my current playthrough of Factorio, mostly because, for me, modding scratches the same itch that actually playing the game does.

Soon after the 1.0 launch this happened to me again. I picked up the latest version of Krastorio 2, got to the power armor point of the game, and was wondering why I couldn’t rotate equipment. Sure, I could probably shuffle everything around in my armour, but sometimes I just want to hit R and slap something into place with minimal effort. A quick search on the mod portal showed me that there was Rotatable Batteries by GotLag; so it was possible, but it hasn’t been implemented for everything.

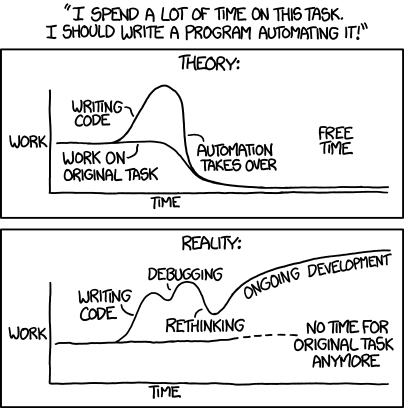

Making a mod work in every circumstance can be a ton of work sometimes. The safe way to handle every case is to hardcode your changes for every situation. That will definitely work, but requires constant monitoring. Having done something like this in the past, I know that it can get quite unwieldly and hard to read. Plus, if one of those other mods changes something, my implementation either outright breaks or is inconsistent with the “supported” mod. So, I’ve recently become a big fan of trying to make my mods as dynamic as possible to avoid this. It should, in theory, also save tons of time, but this doesn’t always work out.

That reality is what I enjoy in Factorio though; the “Oh, but I need to do this thing.” That’s not fun if it’s just adding another mod dependency by adding some string to a list. So, to start a new mod with the aim of being able to rotate any equipment without the need for me to constantly maintain it, I needed to lean on how Factorio loads mods.

In other games where you want to add mods, you have some form of a mod-order list. You, the player, or a program created by modders, needs to tell the game in what order the mods are to be loaded, to make sure everything meshes together well enough to not explode. Factorio achieves this ordering via mod dependencies, but it also goes a whole step further. Factorio doesn’t just load all the mods in order once, it loads them in order three times.

Three times? Seems excessive, right? Actually, it’s a fantastic idea. The wiki explains this in much more detail, but I’ll quickly explain it here. Each mod, in load order, has a settings stage, then a data stage. The settings stage is pretty self-explanatory, and the data stage is for prototype data, such as items, entities, and recipes. This cycle then repeats two more times. Mods specify what to load at each iteration of the cycle. Modding conventions recommend that prototypes all be added as early in this process as possible. This allows for mods that want to implicitly rely on other mods to do it without needing to know they exist. For example, the base Factorio mod does this for barreling of liquids.

This is how the community has the giant overhaul mods that entirely rework all recipes; they just do it in a later data stage to every single recipe in the game. No large lists of mods that need maintenance, no “This mod needs to be loaded last.”

This is how I am able to make my mod able to rotate any equipment. I can just move my checks for equipment that needs a rotated version to a later data stage, and it should implicitly cover any equipment in the game. No need for me to name mods X, Y, and Z as dependencies, or for the player to manage anything at their end; it just works. No constant management for name changes, unless there’s a more complex problem that I will enjoy tracking down.

With all that in mind, a few days, and a half-finished Krastorio save abandoned, Rotatable Equipment was born.

Contributing

As always, we’re looking for people that want to contribute to Alt-F4, be it by submitting an article or by helping with translation. If you have something interesting in mind that you want to share with the community in a polished way, this is the place to do it. If you’re not too sure about it we’ll gladly help by discussing content ideas and structure questions. If that sounds like something that’s up your alley, join the Discord to get started!

As next Friday falls on Christmas Day, we decided not to release an issue that week, meaning this is the last issue of Alt-F4 for this year! We’ll be making our glorious return on the first of January with a bit of a special episode looking back at the how the project has developed so far, with perspectives from various team members about the work they’ve been doing. Should be fun.