Alt-F4 #37 - Combinator Crash Course Continuation 28-05-2021

On the 37th week during which an issue of Alt-F4 is being released, we present: Issue #37! What a surprise! In it, long-time contributor pocarski is back with yet more very approachable explanations of how you can spice up and optimize your base with but a few combinators!

Combinators 2: Augmented Logistics pocarski

Several weeks ago, I wrote an article about using combinators to improve specific builds. This time we’ll take a look at ways to apply the circuit network more generally, to make your whole factory more efficient. We will look at the pitfalls of conventional design, we will come up with ways to solve them, and we will implement those solutions using the circuit network. Such improvements can be done to both bots and trains, and the circuitry is so simple it almost doesn’t require decider combinators at all. Let’s dive right in!

Bots: Network-to-network interface

We’ve all had this issue: you create more bot demand, and suddenly all the bots from the far end of your base decide it’s a good idea to travel thousands of tiles across roboport-less areas. In the best case, this will cause mild frustration at the striking similarity to real-life delivery services, and in the worst case, bots will keep getting destroyed by biters, or turning around part way through to charge at the roboports they just left, leaving you with no throughput whatsoever. This happens when your logistic network has an inward-facing corner, creating a huge logistics-deprived area, which dumb straight-line-pathing bots will immediately start cutting right through.

So, to avoid this, a rule was written: “Thou shalt not create concave logistic networks”. Sounds simple, right? Just have your base be a massive rectangle of roboports, and there will simply be no corners to cut. This is a valid solution, but it puts very significant constraints on your expansion, since you’ll be forced to expand the rectangle to cover all of your newly-acquired real estate. This causes situations where your actual base only takes up a tiny fraction of the area covered by your logistic network.

A much better way to approach this issue is to separate your networks. Essentially, instead of making one huge rectangle, you make a bunch of unconnected smaller ones, which you can then arrange to cover any shape you want. This way, any single network is still convex, meaning bots will never leave the roboport coverage. That’s a good solution, but how does one get items to travel across the gaps between networks? This is where circuits come in.

Let’s construct two networks with a one tile gap in between, and call them network A and network B. The items will cross this gap using a stack inserter placed between a requester chest and an active provider chest. For any items we want to move from A to B, we should set the request on A’s requesters to be the amount of items we wish to transfer. We can transfer items from B to A in a similar way.

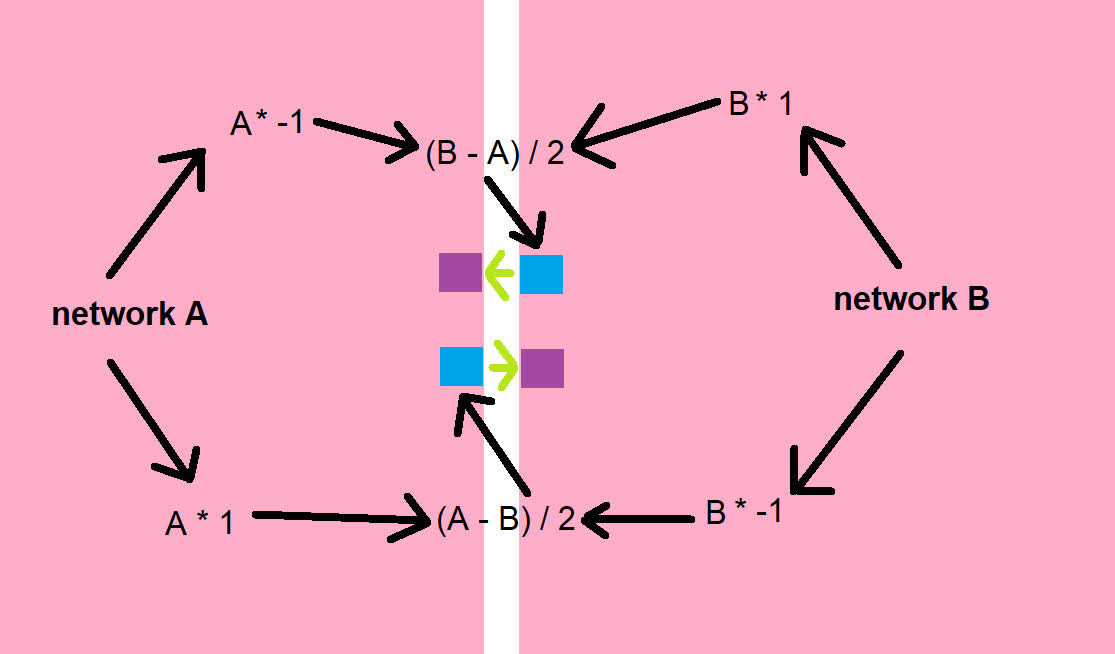

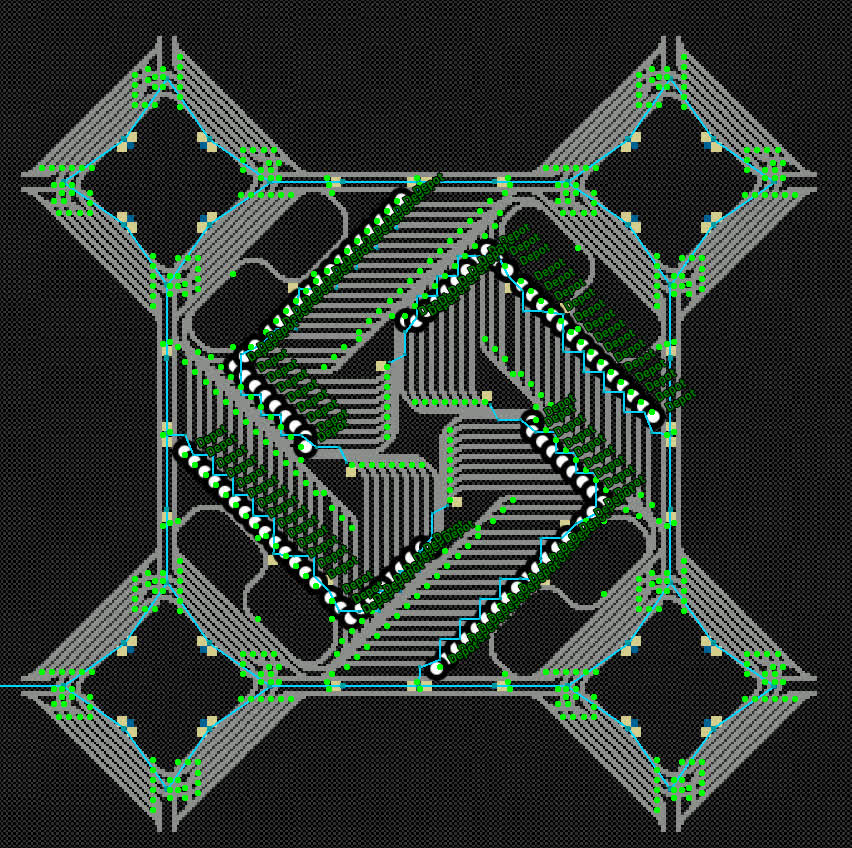

While we can design complex ways to figure out exactly how much of what needs to go where, we’ll stick to a simple solution that works well enough for most purposes: keep both networks at equal amounts of items. To do this, we will determine half of the difference between network contents of each item, and force the network with more of that item to send that many of them to the network with less of that item. Here is a crappy diagram outlining this idea:

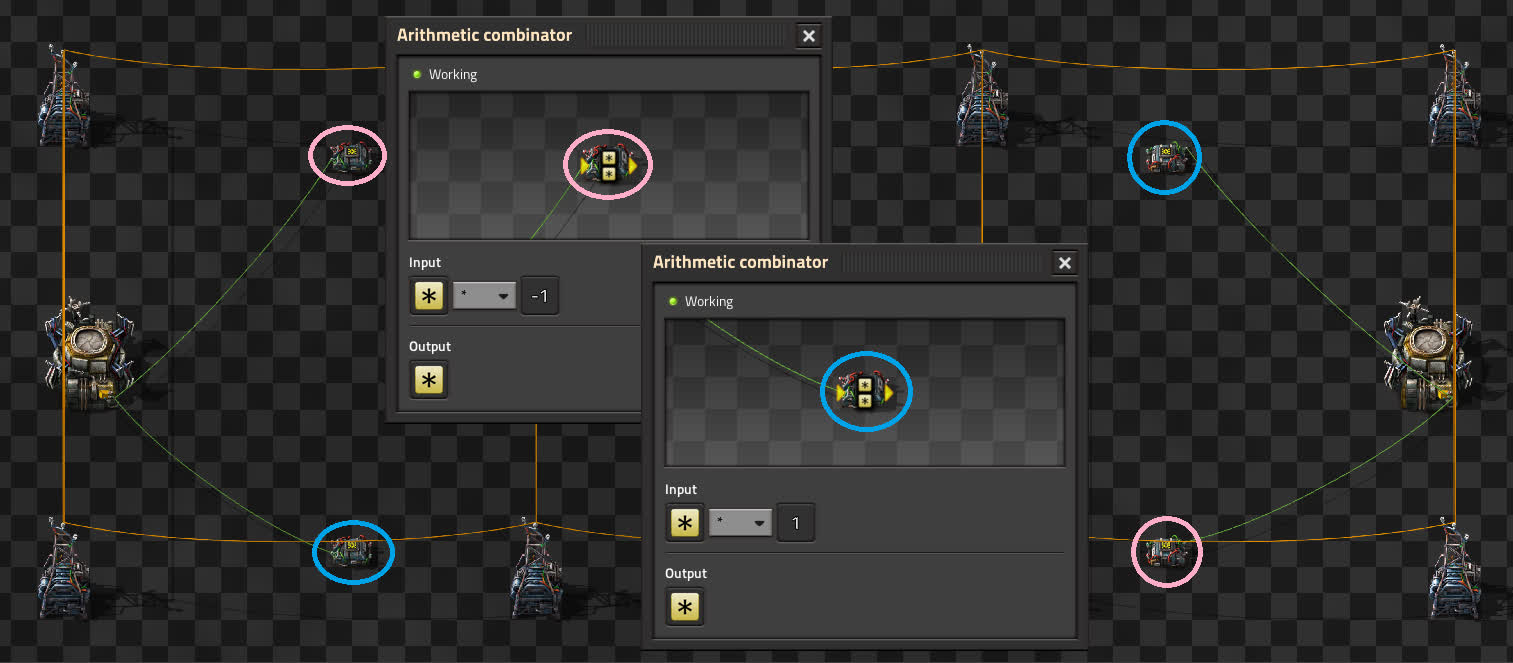

We connect a roboport in network A to a pair of arithmetic combinators, one multiplying by 1, and the other multiplying by -1. This will give us a positive and a negative value for the items in the network. We do the same for network B.

We then connect the negative value of one network to the positive value of the other. This will give us the difference between their contents. We then divide this value by 2 and feed it to the requesters. It’s important that the chests on the side with more items get a positive value, or else the system will do the exact opposite of what we want. It’s also important to round up the value to your robot cargo size, or else they can be flying back and forth forever trying to fix a two item difference by moving four items at a time.

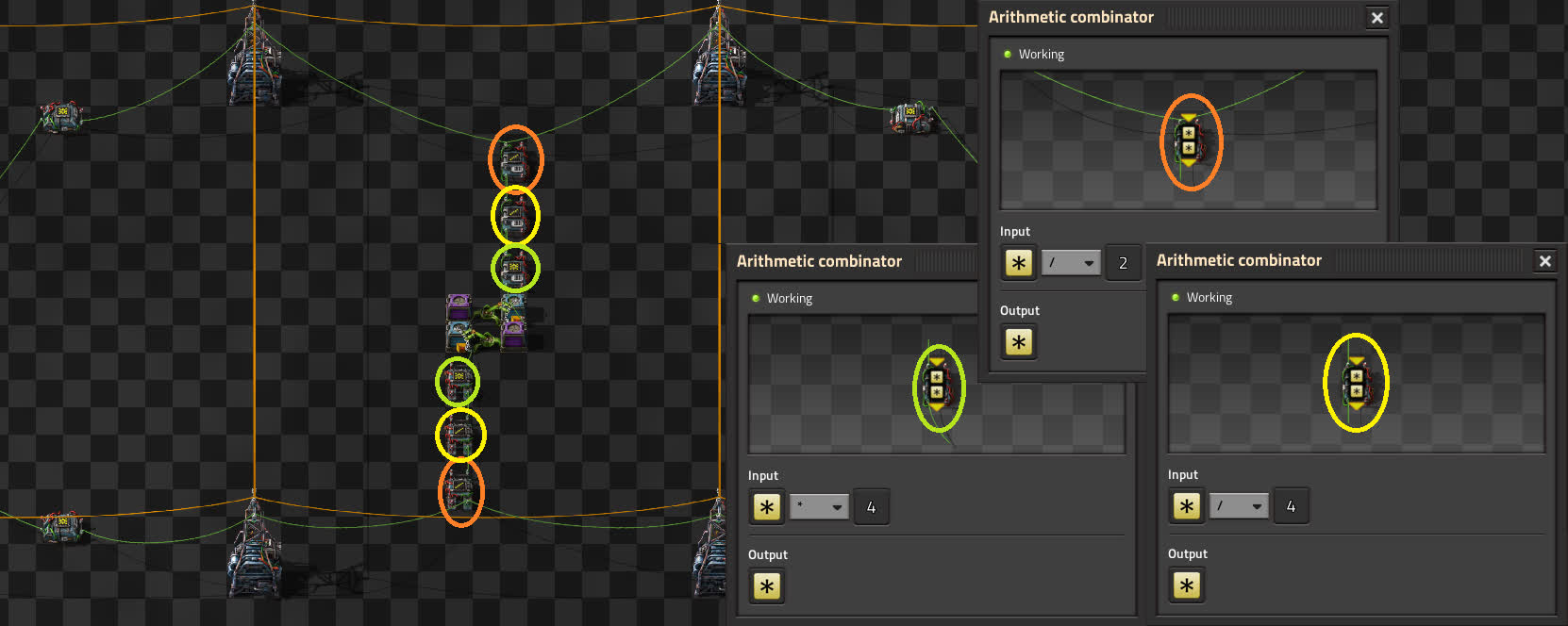

Because one inserter going each way is a bit slow, we can add more. If we just blindly add more chests, then the request of each one will be half the difference, meaning the actual request will be several times more than it’s meant to be. We need to divide the incoming difference by the number of chests, and also add the remainder on to one of the chests. Once again, rounding up to robot cargo size is paramount. This rounding does mean that networks are not going to become strictly equal, but it’s a necessary sacrifice.

This circuit will now do its best to keep the networks’ contents level, with an error of a couple of items. The bots will do a bit of back and forth, because there is a delay between items being removed from one network and added to the other, which means it overcorrects slightly at first. With more than two networks, not much changes. Because each pair of networks tries to equalize the item counts, all items gradually spread more or less evenly through the whole system.

This circuit is infinitely adjustable and customizable. You may add a biasing factor to have the network contents be in a specific ratio, or you may add conditions for when to apply the bias and to what items, and whatever else you can figure out how to do. In my opinion, that is an even more important feature than the simplicity.

Trains: Vanilla LTN analogue

Moving on from bots to trains then: Trains are very powerful, but trains are also dumb. In a complex system with many stations having the same name, you’re pretty much forced to use circuits because otherwise, trains will keep pathing to the same stations, overcrowding them while starving the rest. The conventional way to control train pathing was to disable stations that don’t need trains, forcing trains to path somewhere else. This is, however, a very crude and inefficient method, with multiple issues: trains repathing inside junctions may cause deadlocks, a single station being enabled triggers an avalanche of trains, and the extra trains from that avalanche create unnecessary traffic. There are also existing circuit systems, such as Haphollas’s Vanilla Train Network, which alleviated some of those problems, but still not all of them.

The popular way to avoid all this mess is to use mods. One of the most popular and influential mods for Factorio is LTN, or Logistic Train Network. It essentially implants a logistic bot’s brain into your trains, and gives your stations the functionality of provider and requester chests. You just set what each station wants and the trains will figure the rest out themselves. Needless to say, the mod allows colossal improvements in efficiency. One would expect such a fundamental change to the system to be nearly impossible to recreate with combinators, and they would be correct. It is however extremely easy to create a much simpler, albeit somewhat less efficient, version of LTN using circuits.

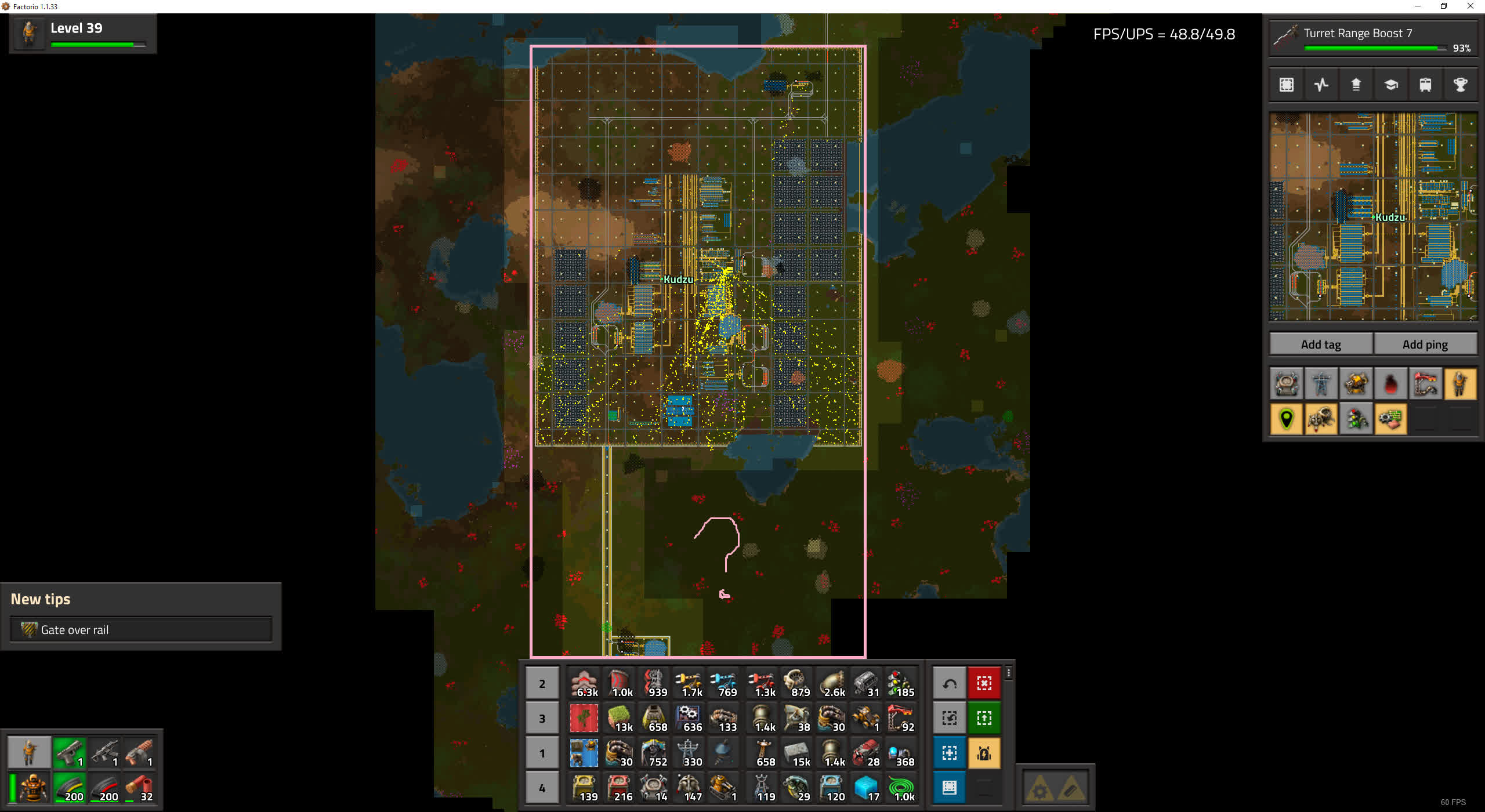

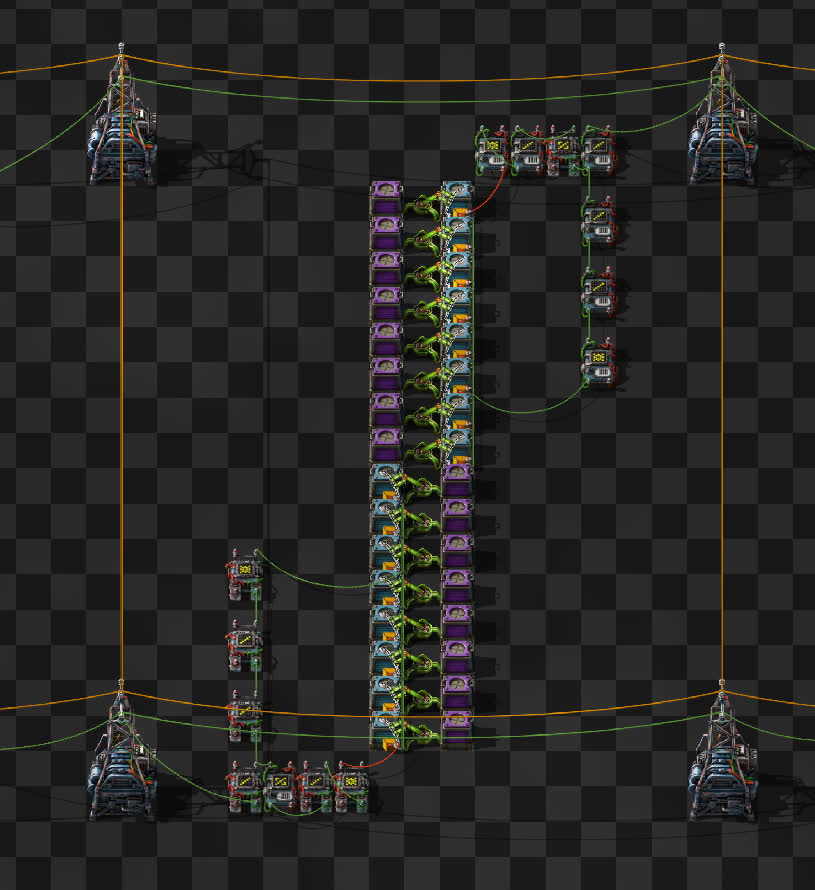

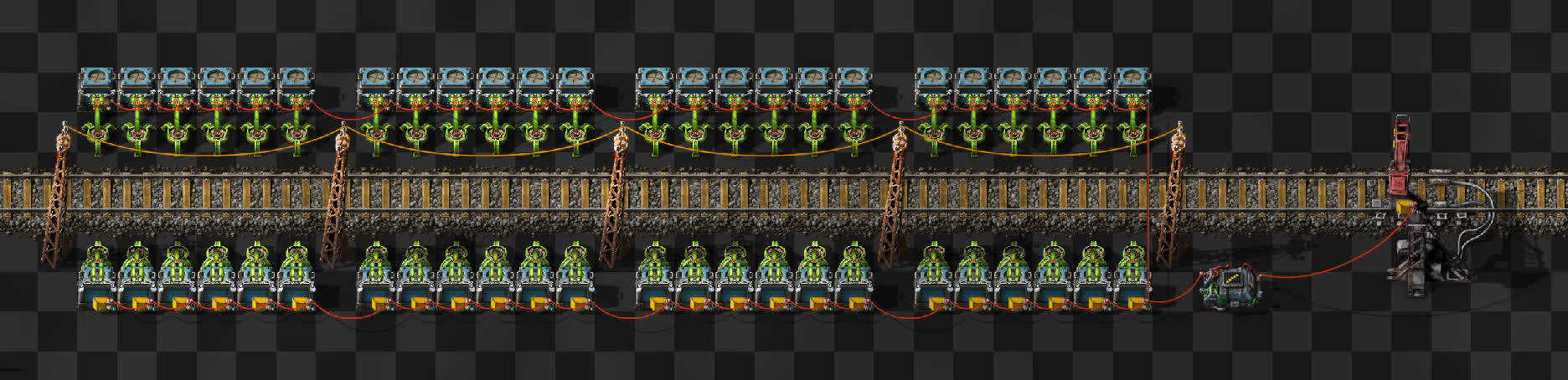

Today, I introduce the “Train Limit Dispatcher and Requester”, or TLDR. It is a set of very basic circuits that multiple people invented independently, making use of the train limits that were introduced in 1.1 to act as train request flags. The major simplification is that unlike LTN proper, in the TLDR system almost every train or station is dedicated to a single resource. The logic is simple: For every provider station, calculate the number of “train loads” you have in storage, and set that as your train limit. For every requester, do the same with the difference between request and contents. Each train then just goes between provider and requester with “cargo full” and “cargo empty” conditions.

TLDR solves all the problems that the classic station-disabling solution has. Trains will never cause deadlocks by repathing inside junctions, since unlike disabling a station, changing its train limit does not force a repath. An excess amount of trains will never be released into a station, since only as many as the train limit allows will be able to leave. No train avalanching means less traffic, higher throughputs, and less trains needed, which also means better game performance.

However, nothing is quite as simple as it sounds. For example, if a train unloads at a requester, but no provider is ready, then it just stands there, starving the requester. This means we need a central depot, so trains always have somewhere to go to free up a requester station. The depot can be as bare bones as it gets: just a bunch of stations with train limit at a constant 1, and some refueling inserters. Trains now also go from requester to depot to provider, stopping in the depot for a short time. Some trains may stop in the depot after leaving the provider too, for example if the provider is really far away.

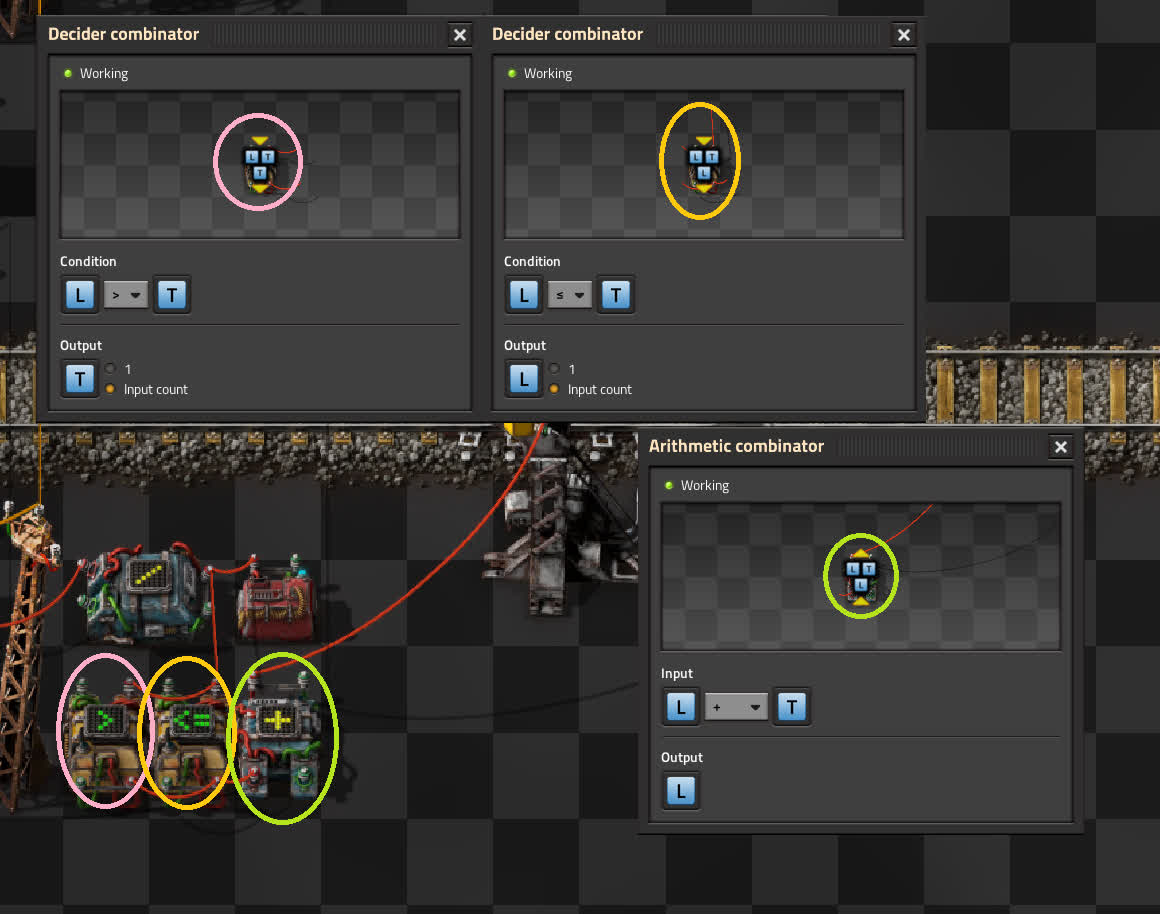

But wait, there’s more! Waiting space in stations is not unlimited, and if too many trains are requested at once, they might start queuing on tracks that shouldn’t have anything queuing on them. To fix this, we add two decider combinators. Those will check if the requested train amount is greater than a certain constant. If it isn’t, the request goes straight through. If it is, the constant is output instead. Their outputs are summed, simply because the constant and train limit use different signals, and they need to be the same signal. That sum is then given to the station as the train limit.

This circuit, just like the first circuit from this article, is customizable. For example, you could have requesters automatically determine and set their own requests, or you could have something completely independent controlling their requests, or you could even change the amount of items loaded into the train. Basically, any constants that the system takes, you can turn into dynamic values, controlled by each other, some independent circuit, or manually even. You could also mess with the train schedules and conditions, for example by making stations kick out trains as soon as their requests are fulfilled, or have a train handle more than one resource.

Conclusion

The circuits given here are intended both as final usable products, and as foundations for your own circuit projects. I would say they are similar to unpainted figurines: you can still get a lot out of them in the form you got them, but you have limitless possibilities as soon as you break out some creativity and skill. There are intentionally no blueprints in this article, because its goal is not just to give you some neat circuits, but also to get you to understand them better. Good luck wiring!

Contributing

As always, we’re looking for people that want to contribute to Alt-F4, be it by submitting an article or by helping with translation. If you have something interesting in mind that you want to share with the community in a polished way, this is the place to do it. If you’re not too sure about it we’ll gladly help by discussing content ideas and structure questions. If that sounds like something that’s up your alley, join the Discord to get started!