Alt-F4 #42 - The Meaning of Automation 16-07-2021

In this week’s issue #42 of Alt-F4, after previously investigating the games that influenced Factorio, we’ll now be looking at how Factorio influenced the automation genre as a whole, if that’s even a thing. Maybe it isn’t. After 7.5 million years of contemplation, Nanogamer7 has an answer, and it might surprise you.

The Best of Its Genre – The Influence of a Game Nanogamer7

A few months ago (in issue #34) I tried to find the origins of Factorio, and with it the origins of the automation genre. But since the time Wube pioneered this genre in 2013, many games adapted and embraced its ideas, like Satisfactory and Dyson Sphere Program, but also games more focused on survival like Astroneer, later versions of Minecraft and more recent mods for it. In this article I want to explore what became of the automation genre, and how automation games are differentiated to survival games with some automation.

Part 1: The Big Three

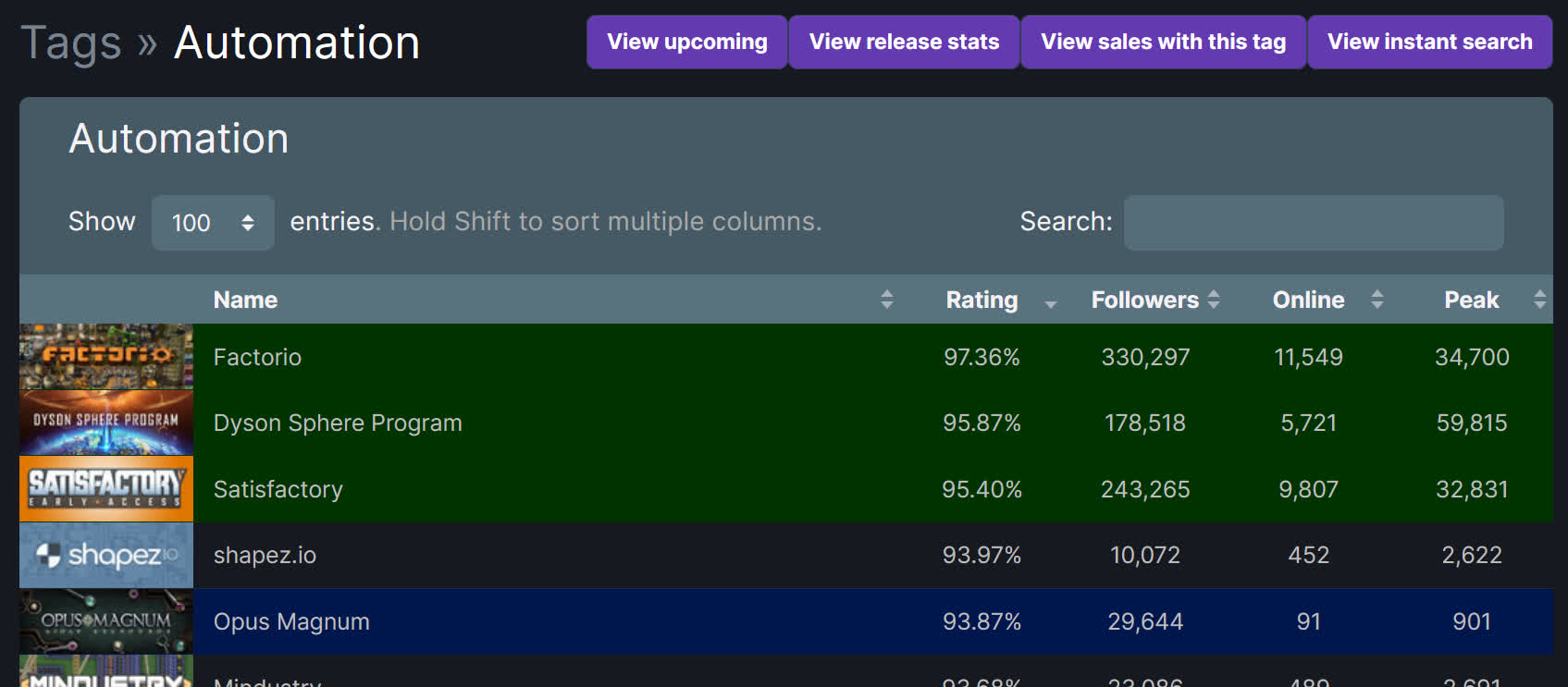

When you ask someone to name some automation games other than Factorio, the most common response you’ll get are Satisfactory and Dyson Sphere Program. Together with Factorio, they are even regarded as the (un-)holy trinity of automation by some players. But what makes these games stand out from the rest (apart from their rating, the highest among all games on Steam with the “automation” tag)?

- All three games are set in an open world and you, the player, are an entity in it, building the factory. Neither of these are required for automation, as for example shapez.io perfectly works without a playable character, and there a plenty of games like Opus Magnum that are in a level-based puzzle environment.

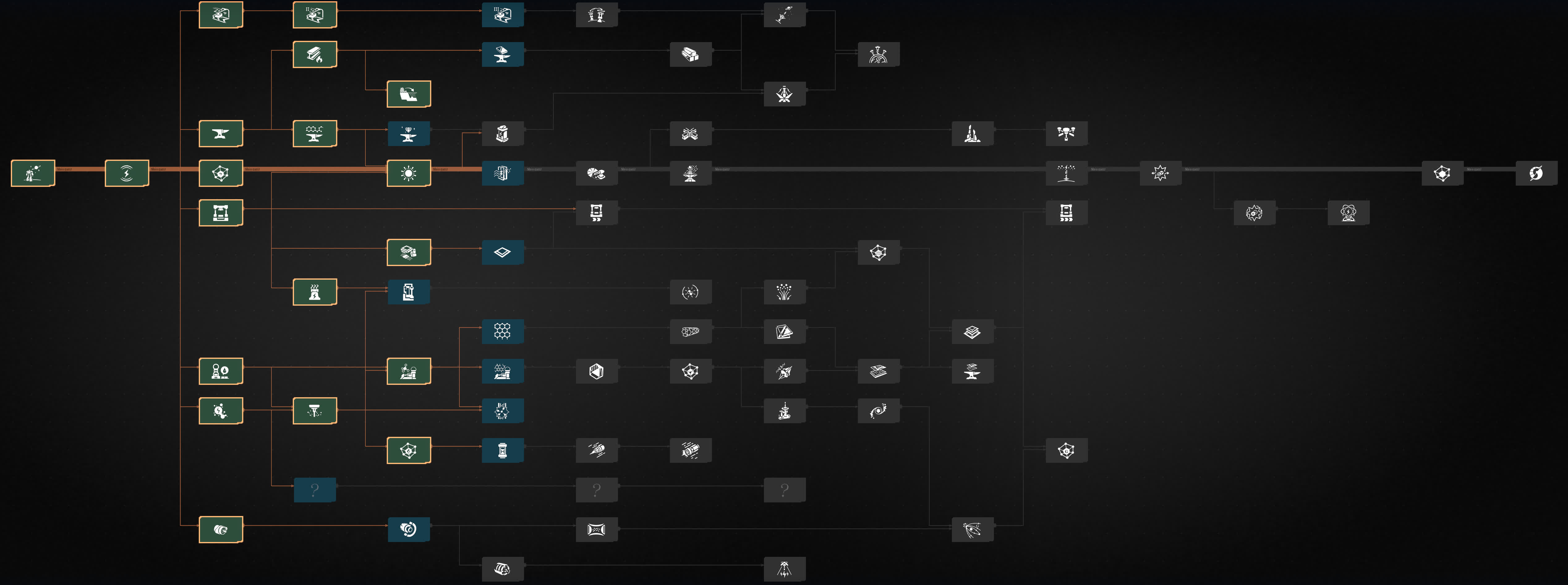

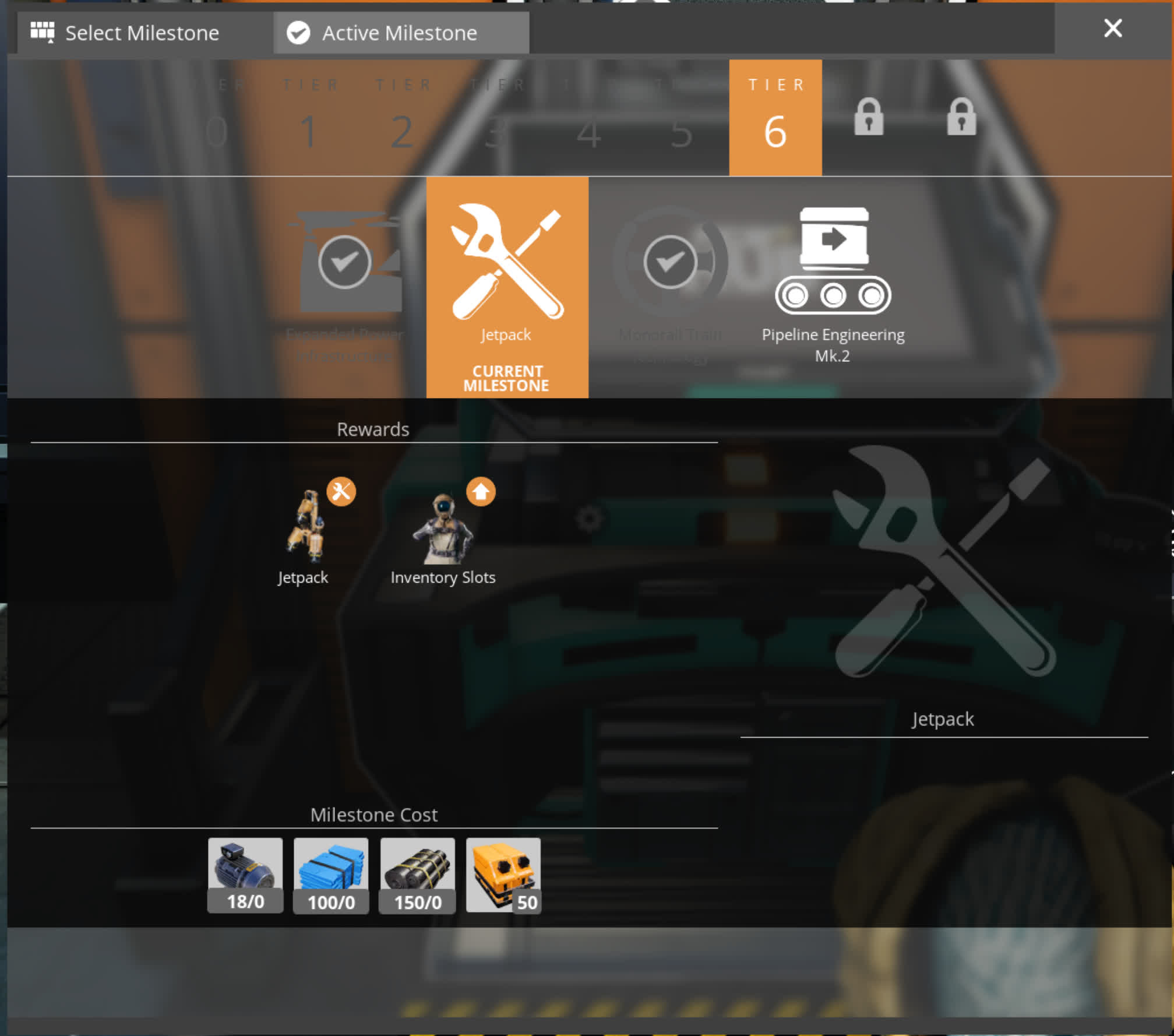

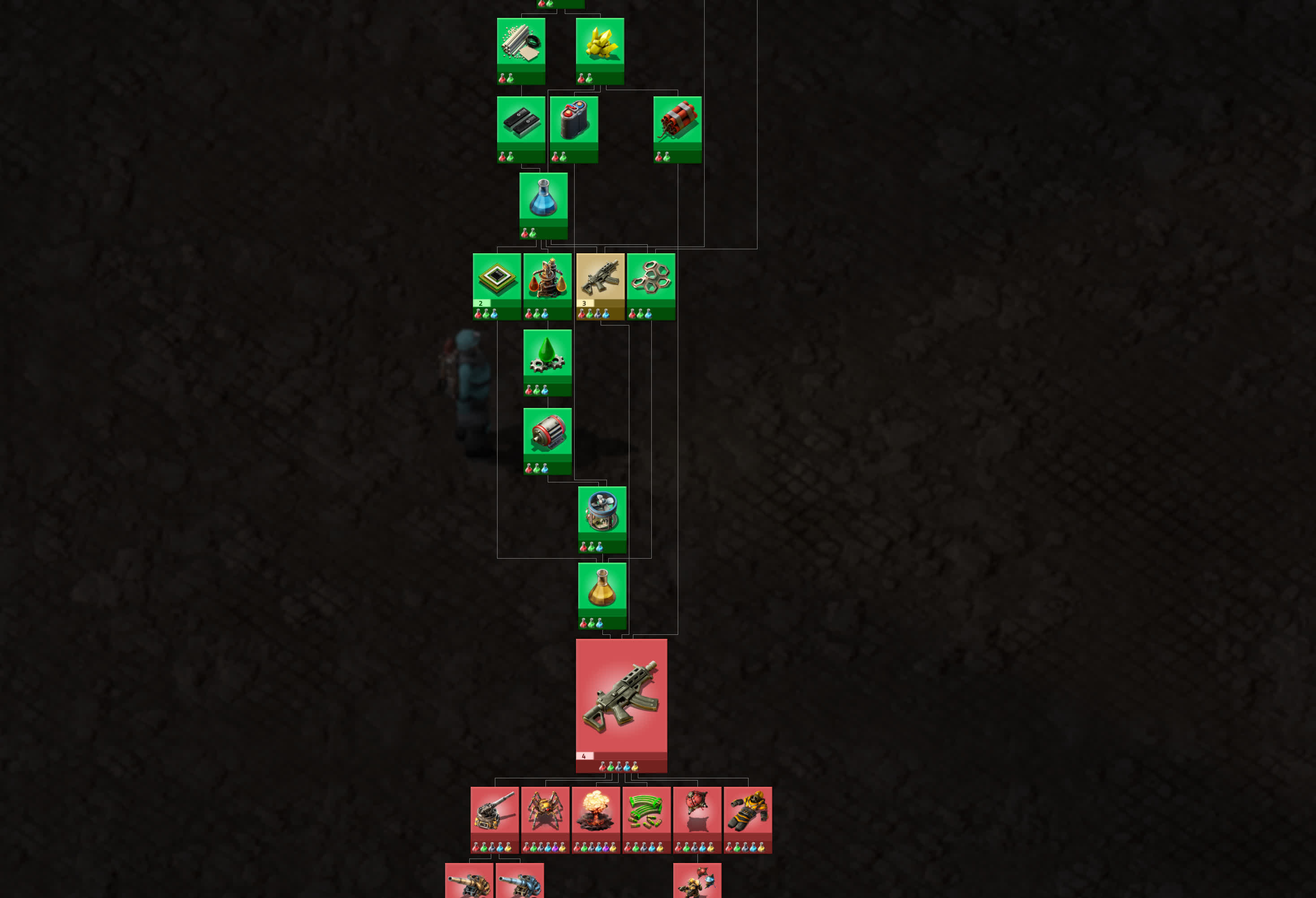

- Your progression is mainly through a skill/technology tree (be it a very shallow one in Satisfactory); Special technology to send through a space elevator in Satisfactory, research matrixes in DSP, and finally, the bottle-shaped science packs in Factorio. Most open world (survival) games feature some sort of skill tree, but acquiring new points rarely features a connection to the game world. The factories, however, have to be built primarily for the tech tree itself; you don’t have some requirements to limit your progress in the “story”, the requirements are directly tied to the progress towards the final goal.

- And finally, all three games mainly challenge your knowledge and understanding of logistics. While the spaghetti of some bases might suggest otherwise, space isn’t actually an issue (or at least not a big one) due to the open world, but getting massive amounts of raw resources from a mining outpost back to your main base requires you to overcome obstacles like mechanics, throughput, and environment. And it can get even more challenging, for example moving production to said outpost to export the most dense/compact products (see Alt-F4 #7) uses complex ratios to get the most efficiency. This challenge might be a direct result of the open-world nature of these games, but especially long range trucks and trains provide a much needed “unknown” variable to the defined ratios (unknown as in not as obvious as items per second on belts), as well as a challenge, a bottle neck scaling inversely with production.

The different research trees, with DSP more similar to Factorio, and Satisfactory in its shallow tier system.

Apart from the similarities in gameplay, the three games also feature a remarkably similar scenario of the player being dropped on an empty planet; however this is probably of the most obvious narrative reasons for the player to start from scratch. This article won’t elaborate on the story behind the games, but rather focus on the gameplay itself.

These are some of the most important similarities between the three games. There are definitely more smaller ones, or in areas other than gameplay, but if you get to the core of it these three are what define the games, trains unfortunately not being one of them. But how do games not generally regarded as automation fall into this scheme?

Part 2: Automation in Other Games

Speaking of scenario, there is a fourth game with this scenario, with a similar theme of multiple, small planets, with a great rating, with the “automation” tag on steam, and it is arguably even more popular than the other three games: ASTRONEER. Why didn’t I mention it before? It certainly has a similar scenario, you can automate large parts of your production, and so on.

Let’s get back to the previous article, what does automation even mean?

One could loosely define automation as “making stuff that makes stuff”

— Nano

Keep in mind this is only one possible definition of the genre, but it already runs into some problems. For example Nanocarbon Alloy, one of the most important Astroneer endgame materials, already fails to be automated at one of the most basic steps of getting all required resources together—which isn’t necessarily bad though, the game wasn’t developed as an automation game. The auto arm—and with it some other tools to automate—only got added in version 1.13, a full year after the original 1.0 release of the pure survival game.

Many (survival) games feature some sort of automation today: Minecraft’s hopper, added with version 1.5 in early 2013 is the first example of a simple machine to machine transfer I could find, and might have influenced Factorio’s inserter too, but ASTRONEER’s auto arm, the auto miner, the conveyors in TerraTech, the belts in some Overcooked levels are all reminiscent of similar Factorio mechanics, and all got released after Factorio first got popular. And then there are mods: Basically every tech Minecraft mod since 1.6.4 (although those might also be influenced by the earlier Minecraft mods) features automation.

Still, none of the games above have automation as the defining mechanic, it only gets complimented by it. You might spend way too long building complex machineries, intricate factories, and tightly packed rovers, but none of them progress your gameplay directly. You still need to explore, discover, fight, and decorate your way further towards your final goal. There can however be made an argument for SkyFactory, one of my favourite Minecraft mod packs, which circumvents the problem of exploration by having nothing to explore. It still allows you to encase your factory in nice blocks, decorate it with flowers, which is the other main goal of Minecraft, only coming as a secondary possibility in Factorio.

How do games not generally regarded as automation fall into the scheme from part one then? Logistics present themselves in the form of inventory management, and is a common part of survival games, as is the open world. And the skill tree, which the automation games make completely unfeasible to hand craft, is just supplemented by automation in the other games. This supplementation is the important part, adding automation as another mechanic among many has become popular with the popularity of automation games.

Part 3: Simulation, Idle, and Puzzle Games

Most games so far are in some way an open-world survival or sandbox game, however there is a subgenre of automation most of us have come on contact with and regularly play: Designing the assembly line itself. There are numerous automation puzzlers which exclusively focus on that part of automation. One example is Opus Magnum, as already mentioned, or factori, a game scoring one of the first places in the recent GMTK 2021 game jam. Both fit the definition (“you make stuff that makes stuff”) chemicals in one, and letters in the other. Does Emergency Protocol (there area lot of puzzle games in game jams btw) fit the definition? You make a pattern that makes a path? In its core it sounds like automation—you tell a little robot what to do (program it), and it repeats your commands—but that also sounds similar to idle games—set something up, and it does a job for you while you are away.

Speaking of which, idle games aren’t really considered automation games, and neither are management games or simulation games, as I discussed in my last article. But then again, there is the meme of automating Factorio itself, which some players have successfully done. On a more serious note, some players really do play Factorio as a management game—city block blueprints often have every assembly line, every problem already solved, your job now is to balance the different resources and power, and manage the factory on the larger scale.

Conclusion

To summarise, automation still isn’t a type of game like “puzzler”, but it can definitely be the defining genre. However it is still possible to add automation to game, without having it at its core. That being said, my last article left automation a bit more open, and I hope I could give a more SATISFACTORY definition and conclusion this time by FACTORIOing in more recent games.

Contributing

As always, we’re looking for people that want to contribute to Alt-F4, be it by submitting an article or by helping with translation. If you have something interesting in mind that you want to share with the community in a polished way, this is the place to do it. If you’re not too sure about it we’ll gladly help by discussing content ideas and structure questions. If that sounds like something that’s up your alley, join the Discord to get started!